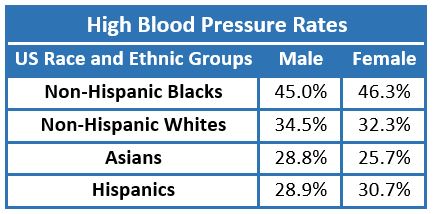

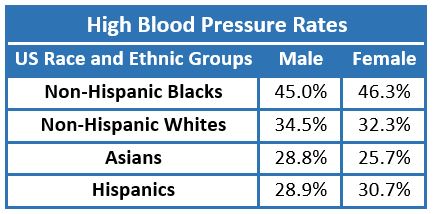

Blacks have the highest rates of hypertension among all racial groups in the US.1 It is difficult to determine the degree to which these disproportionately high rates are due to physiologic, genetic, social, or behavioral factors.

Table: Age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension based on the American Heart Association’s 2018 heart disease and stroke statistics.

Genetic Risk Factors

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) can look for genetic markers that are associated with disease incidence, including hypertension.2–4 However, simply finding genetic loci that can be linked statistically to the risk of hypertension does not prove that genetic differences cause an increase in the risk of hypertension in a given population. Other factors, such as environmental, psychosocial, and behavior differences that influence hypertension and also occur disproportionately within a given population must be considered as well as possible explanations for disparities in hypertension. While this work continues, there is insufficient evidence to predict the degree to which genetic ancestry determines a risk for the development of hypertension.

Marden et al. studied a cohort (n=998) of older non-Hispanic US blacks who had provided genetic data to the Health and Retirement Study.5 Their goal was to estimate the degree to which genetic ancestry, as well as self-reported behavioral and socio-economic factors influence the risk of hypertension among US blacks. Their results suggest that while African ancestry is strongly related to self-reported hypertension, the relationship was cofounded by several social determinants of health such as region of birth, childhood disadvantage, education level attained, and income which themselves may have indirect effects on hypertension risk.

Social and Behavioral Risk Factors

Until a large randomized control study is conducted that considers multiple predictors of hypertension risk simultaneously, it is difficult to say with certainty which factors have the greatest influence on blood pressure rates.6,7 Population statistics in the US demonstrate that as a group black Americans have lower income levels and other measures of socioeconomic status than whites in America.8 Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between blood pressure and specific social and behavioral factors in African-American populations that may be influencing the higher rates of hypertension in this population. These include the link between blood pressure and socio-economic status,9,10 educational attainment,10,11 perceived racial discrimination,12–15 psychosocial stress,16,17 diet,18–21 and exercise.14 African-Americans as a group develop high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease (CVD) at a younger age than non-Hispanic whites.22 However, randomized controlled studies that provide solid evidence to explain possible environmental and lifestyle factors that might influence racial disparities in blood pressure rates are lacking.

Control of Blood Pressure Once Diagnosed

Data from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study showed that black participants were more aware of their hypertension than white participants (odds ratio [OR] 1.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] [1.07 –1.59]).23 They were also more likely to be receiving treatment for their high blood pressure (OR 1.69, 95% CI [1.40 – 2.05]). Treated blacks, however, were less likely to achieve blood pressure control than treated whites (OR 0.73, 95% CI [0.64 – 0.83]). Control rate disparities by race/ethnicity in other clinical trials have sometimes been more modest,24 but similar discrepancies in blood pressure control between non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites persist in population-based data.25 In the 2007-2014 NHANES data, 41.6% of non-Hispanic black males and 53.4% of non-Hispanic black females had achieved blood pressure control, compared to 53.9% and 58% for non-Hispanic white males and females, respectively.26 Data from the most recent US heart disease and stroke statistics demonstrate that blacks with hypertension were more likely to have treatment-resistant hypertension (19.0%) than non-Hispanic whites (13.5%) and Hispanics (11.2%).1 Treatment-resistance is defined as the persistence of high blood pressure after treatment with three or more antihypertensive medications.27 Better blood pressure control in black Americans has been achieved in some large treatment and control programs,28,29 suggesting that systems problems in the delivery of health care may at least partially explain hypertension control disparities. A Brazilian study examined factors associated with blood pressure control and found that low household income was inversely associated with blood pressure control while ancestry (African, European, or Native American) was not.30 Relatively few black participants have been studied for gene–treatment interactions in GWAS studies.31 More study is needed in black populations to clarify why effective treatment of high blood pressure remains elusive in this population.

Implications for Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality Rates

The higher rates of blood pressure among African Americans in the US translates into higher death rates from CVD and stroke.1 The death rate from CVD for non-Hispanic blacks is 557.9 per 100,000 persons over 35 years of age compared to 430.5 per 100,000 in non-Hispanic whites. The death rate from stroke for non-Hispanic blacks is 100.5 per 100,000 persons over 35 years of age compared to 70 per 100,000 in non-Hispanic whites. Even more concerning is the fact that, in one clinical trial at least, the risk of stroke in African Americans was shown to be three times the risk in non-Hispanic whites with the same level of systolic blood pressure.32 Explanations for these persistent differences in hypertension rates and CVD mortality are still not well understood.31

References

- Benjamin E, Virani S, Callaway C et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 137: 67-492.

- Franceschini N, Fox E, Zhang Z, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of blood-pressure traits in African-ancestry individuals reveals common associated genes in African and non-African populations. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 93 (3): 545-554.

- Fox ER, Young JH, Li Y, et al. Association of genetic variation with systolic and diastolic blood pressure among African Americans: the Candidate Gene Association resource study. Hum Mol Genet 2011; 20 (11): 2273-2284.

- Kato N. Ethnic differences in genetic predisposition to hypertension. Hypertens Res 2012; 35 (6): 574-581.

- Marden JR, Walter S, Jay S, Glymour MM.African Ancestry, social factors, and hypertension among non-Hispanic blacks in the health and retirement study. Biodemography Soc Biol 2016; 62 (1): 19-35.

- Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social Determinants of Risk and Outcomes for Cardiovascular Disease A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 132 : 873-898.

- Schultz W, Kelli H, Lisko J et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 2018; 137 (20): 2166-2178.

- US Census Bureau. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2017.

- Grotto I, Huerta M, Sharabi Y. Hypertension and socioeconomic status. Curr Opin Cardiol 2008; 23 (4): 335-339.

- Lewis MW, Khodneva Y, Redmond N, et al. The impact of the combination of income and education on the incidence of coronary heart disease in the prospective Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke ( REGARDS ) cohort study. BMC Public Health 2015; 15 (1312): 1-10.

- Non AL, Gravlee CC, Mulligan CJ. Education, genetic ancestry, and blood pressure in African Americans and whites. Am J Pub Heal 2012; 102 (8): 1559-1565.

- Brondolo E, Love EE, Pencille M, Schoenthaler A, Ogedegbe G. Racism and hypertension: a review of the empirical evidence and implications for clinical practice. Am J Hypertens 2011; 24 (5): 518-529.

- Brondolo E, Libby DJ, Denton E-G, et al. Racism and ambulatory blood pressure in a community sample. Psychosom Med 2008; 70 (1): 49-56.

- Klimentidis YC, Casazza K, Willig AL, Allison DB, Fernandez JR. Genetic admixture , social – behavioural factors and body composition are associated with blood pressure differently by racial – ethnic group among children. J Hum Hypertens 2011; 26 (2): 98-107.

- Dolezsar CM, McGrath JJ, Herzig AJM, Miller SB. Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: a comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychol 2014; 33 (1): 20-34.

- Ford CD, Sims M, Higginbotham JC, et al. Psychosocial factors are associated with blood pressure progression among African Americans in the Jackson heart study. Am J Hypertens 2016; 29 (8): 913-924.

- Mujahid MS, Diez Roux A V, Cooper RC, Shea S, Williams DR. Neighborhood stressors and race/ethnic differences in hypertension prevalence (the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Am J Hypertens 2011; 24 (2): 187-193.

- Bartley K, Jung M, Yi S. Diet and blood pressure: differences among whites, blacks and Hispanics in New York City 2010. Ethn Dis 2014; 24 (2): 175-181.

- Stamler J, Brown I, Yap I, Al E.Dietary and urinary metabonomic factors possibly accounting for higher blood pressure of African-Americans compared to white Americans – – the INTERMAP study RR. Hypertension 2013; 62 (6): 1074-1080.

- Graudal NA, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jurgens G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2017; 4 : CD004022.

- Svetkey LP, Simons-Morton D, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure: subgroup analysis of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159 (3): 285-293.

- Carnethon M, Pu J, Howard G, Albert M, Anderson C, Bertoni A. Cardiovascular health in African Americans. Circulation 2017; 136 : 393-423.

- Howard G, Prineas R, Moy C, et al. Racial and geographic differences in awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study. Stroke 2006; 37 : 1171-1178.

- Cushman WC, Ford CE, Einhorn PT, et al. Blood pressure control by drug group in the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008; 10 (10): 751-760.

- Gu Q, Burt VL, Dillon CF, Yoon S. Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension: the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2001 to 2010. Circulation 2012; 126 : 2105-2114.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. Accessed: Mar 8, 2019.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task F. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71 (19): e127-e248.

- Sim JJ, Handler J, Jacobsen SJ, Kanter MH. Systemic implementation strategies to improve hypertension: the Kaiser Permanente Southern California experience. Can J Cardiol 2014; 30 (5): 544-552.

- Fletcher RD, Amdur RL, Kolodner R, et al. Blood pressure control among US veterans: a large multiyear analysis of blood pressure data from the Veterans Administration health data repository. Circulation 2012; 125 (20): 2462-2468.

- Lima-Costa MF, Mambrini JV de M, Leite MLC, et al. Socioeconomic position, but not African genomic ancestry, is associated with blood pressure in the Bambui-Epigen (Brazil) cohort study of aging. Hypertension 2016; 67 (2): 349-355.

- Whelton PK, Einhorn PT, Muntner P, et al. Research needs to improve hypertension treatment and control in African Americans. Hypertension 2016; 68 (5): 1066-1072.

- Howard G, Lackland DT, Kleindorfer DO, et al. Racial differences in the impact of elevated systolic blood pressure on stroke risk. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173 (1): 46-51.