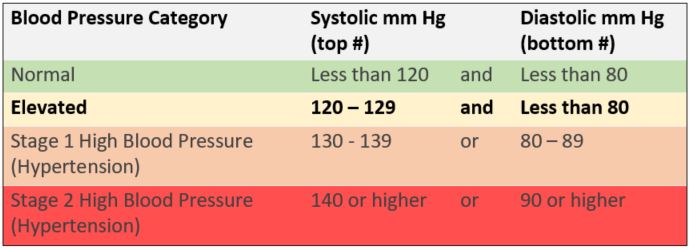

According to 2017 hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA), elevated blood pressure (BP) is defined as 120 – 129 systolic and less than 80 diastolic.1 This is a new category that is distinct from the diagnosis of hypertension or high blood pressure. The risk for heart attack, stroke and other high blood pressure complications begins to increase around 115/75 mm Hg.1-5 The risk doubles for each 20 mm Hg increase in the systolic pressure and each 10 mm Hg increase in the diastolic pressure.

Evidence shows that lowering high BP decreases the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes such as heart disease, stroke, and death.6-9 It may also slow the progression of kidney damage in people with chronic kidney disease for people with hypertension.10 Further, meta-analyses as well as national and international guidelines suggest that for people with high blood pressure, lowering BP decreases risk of these outcomes regardless of method or medication used.6-9

Diagnosis of elevated blood pressure and hypertension is based on an average of two or more careful blood pressure readings on two or more occasions when the patient is relaxed, sitting for more than five minutes, and has not done anything recently to increase BP such as smoke or exercise.1

Doctors should promote nonpharmacological therapy to people with elevated BP and reassess them in three to six months.1 Nonpharmacological therapy includes healthy diet, weight loss, sodium reduction, exercise, enhanced intake of dietary potassium, and moderating alcohol consumption.

References

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2017.

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002; 360 (9349): 1903-1913.

- Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1.25 million people. Lancet 2014; 383 (9932): 1899-1911.

- Reboussin DM, Allen NB, Griswold ME, et al. Systematic review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017.

- Wright JT, Jr., Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373 (22): 2103-2116.

- Ahluwalia M, Bangalore S. Management of hypertension in 2017: targets and therapies. Curr Opin Cardiol 2017; 32 (4): 413-421.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults. JAMA 2014; 311 (5): 507-520.

- Pignone M, Viera AJ. Blood pressure treatment targets in adults aged 60 years or older. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166 (6): 445-445.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, Humphrey LL, Frost J, Forciea MA. Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166 (6): 430-430.

- KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2013; 3 (1): i-150.

.png)