Hypertension does not cause symptoms in most people.1-4 There is a common misbelief among patients that hypertension always causes symptoms, but most people with hypertension have no symptoms.3,4 This lack of significant symptoms and the fact that hypertension is the most common cause of cardiovascular disease is why it has become known worldwide as “The Silent Killer”.3,5,6

It should be noted this PALS article is discussing mild and moderate hypertension, not hypertensive crisis. People experiencing a hypertensive crisis have dangerously high blood pressure (above 180/120 mm Hg) and clinical signs and/or symptoms of serious organ damage.7

Possible Symptoms of Mild or Moderate Hypertension

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that most people with hypertension have no symptoms.3 However, they follow this statement with the acknowledgement that sometimes people can have symptoms, such as headache, dizziness, shortness of breath, nose bleeds, chest pain, and heart palpitations. The WHO also states that these symptoms cannot be relied on to identify people with hypertension.

Studies have tried to determine whether symptoms are caused by high blood pressure and whether symptoms can help identify people for diagnosis. Many studies have found no significant correlation between high blood pressure and symptoms such as headache8-15, dizziness13-15, palpitations13,14, insomnia13,16,17, epistaxis10,18-20, and tinnitus10,14. However, some studies did find an association between high blood pressure and headache21,22, dizziness10, nocturia14, and epistaxis18. Finally, in some studies, high blood pressure is related inversely to symptoms, such as headache11,12 and chest pain23, with fewer people reporting symptoms the higher their blood pressure. This is possibly due to hypertension-related hypoalgesia. Regardless, most studies agree that symptoms are not reliable indicators of blood pressure status.

Hypertension Symptom Study Details

In 1972, Weiss et al. reviewed data from the 1960 to 1962 Health Examination Survey of adults. They analyzed a self-administered medical history form and the blood pressure of 6672 adults.10 They found no correlation between headache, epistaxis, and tinnitus with high blood pressure. Dizziness was found more often only in people with a very high diastolic pressure (>110 mm Hg), and fainting occurred less often in people with higher blood pressure.

A study done by Chatellier et al. of 1771 adults with untreated hypertension examined symptom prevalence in relation to blood pressure levels.14 Mean supine systolic blood pressure ± s.d. was 159 ± 28 mm Hg and diastolic was 94 ± 16 mm Hg. Patients had a mean duration of disease ± s.d. of 7.0 ± 8.1 years. The most reported symptoms were headache (40.5% of patients), anxiety (30.7%), emotivity (29.6%), palpitation (28.5%), dizziness (20.8%), nocturia (20.4%), blurred vision (19.1%), insomnia (17.7%), dyspnea (16.8%), chest pain (15.5%), tinnitus (13.7%), and depression (5.6%) (for all, p<0.001). After adjusting for age, the authors found no correlation between blood pressure levels and headaches, palpitation, dizziness, or tinnitus. In men, after age adjustment, only nocturia increased significantly (p<0.01) with systolic blood pressure. In women, no significant correlations were found for the prevalence of symptoms and blood pressure.

A prospective study of 22 685 adults with high blood pressure found that patients with a systolic blood pressure of ≥150 mm Hg had a 30% lower risk (women risk ratio [RR] 0.7, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.6 – 0.8] and for men RR 0.8, 95% CI [0.7 – 0.9]) of having non-migraine headache compared with those with a systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg.11 In the multivariable adjusted analysis of the cross-sectional study of 51 336 patients, similar trends were found, but to a lesser degree for the relationship between higher systolic blood pressure and lower risk of headache. However, this analysis found an increased risk of all types of headache for men with a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg (odds ratio [OR] 1.2, 95% CI [1.1 – 1.2]) and for migraine-type headache for women with a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg (OR 1.2, 95% CI [1.0 – 1.3]).

The HUNT 2 study from 1995-1997 had 13 852 headache-free adult participants.12 At the time of follow-up for the HUNT 3 study from 2006-2008, 2219 people from the headache-free group had developed any type of headache. Upon analysis, it was found that increasing systolic blood pressure correlated with a decreased incidence of any type of new headache (OR 0.90 per 10 mm Hg increase, 95% CI [0.87 – 0.93], p<0.001). Diastolic blood pressure increases were related to decreasing occurrence of overall headache (OR 0.92 per 10 mm HG increase, 95% CI [0.87 – 1.00], p=0.036).

Middeke et al performed a cross-sectional study of 59 448 participants of which 55 165 were diagnosed hypertensives, 4283 had other diagnoses, and 1399 were the normotensive controls.15 Their results demonstrated that symptoms can occur in hypertensive patients, and the severity of hypertension correlates with increased symptom reports. In this study, up to 52.9% of untreated hypertensive participants with severe hypertension (≥180/110 mm Hg) and up to 56.7% of treated hypertensives reported morning symptoms attributed to hypertension by the authors. Specific symptoms of dizziness (19.6% vs 13.6%) and headaches (17.0% vs 7.4%) were significantly more likely (p<0.0001) in the 2154 untreated antihypertensive participants as compared with the normotensive participants, respectively.

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between hypertension and epistaxis was performed on 10 studies with 9574 participants total.18 Min et al found a significantly increased risk of epistaxis for hypertensive patients (odds ratio [OR] 1.532, 95% CI [1.181 – 1.986]. However, the analysis could not prove a causal relationship between hypertension and epistaxis due to limitations in the available studies and because hypertension did not have a significantly increased risk in cohort studies but did in the case-control studies.

Stewart et al enrolled 9427 adults and collected information about their pain symptoms in four areas: chest, leg, back, and gallbladder.23 The participants were grouped into four blood pressure categories: unaware hypertensives (n=535), previously diagnosed with hypertension but normal blood pressure during study, called aware normotensives (n=7437), diagnosed aware hypertensives (n=520), and normotensives (n=935). The mean age and BMI were higher in hypertensives than normotensives. 25.2% of aware normotensives and 41.9% of aware hypertensives reported current use of antihypertensive medication. This study found that as systolic blood pressure increased, the probability of reporting chest pain (β=-0.009, SE=0.002, Wald=15.78, p<0.05) and gallbladder pain (β=-0.010, SE=0.002, Wald=17.07, p<0.05) decreased in unaware hypertensives. Similarly, for previously diagnosed patients, they found the probability of reporting chest pain (β=-0.006, SE=0.003, Wald=4.18, p<0.05) and gallbladder pain (β=-0.009, SE=0.004, Wald=6.92, p<0.05) decreased as systolic blood pressure increased. In both groups, there was no significant association found between systolic blood pressure and leg or back pain.

Antihypertensive Medication as Source of Symptoms

Some studies examined the prevalence of symptoms between treated and untreated hypertensives and found that certain symptoms like dizziness were more likely to occur in treated patients, suggesting that the symptom was related to the antihypertensive medication rather than the blood pressure itself.24,25 Vandenburg et al. found that people on antihypertensives are more likely to be on additional medications for other conditions.25 They concluded that other conditions and medications need to be considered when a hypertensive patient reports symptoms.

Hypertension Diagnosis Increases Patient Perception of Symptoms and Illness

Studies have shown that patients who have been told they have hypertension (labeled as hypertensive) are more likely to report symptoms when questioned and perceive a poorer quality of health than undiagnosed hypertensives.13,23,26,27 This misconception that hypertension is an illness with symptoms adds to people’s anxiety and health concerns. One qualitative study of African American patients demonstrated that people who don’t experience symptoms may not take their medication because they think the condition doesn’t need treatment.28 The authors of the 2003 JNC-7 hypertension guidelines recognized this when they stated that as part of patient education, doctors should emphasize that people cannot tell if their blood pressure is elevated by feelings or symptoms; blood pressure measurement is required for determination.29

In the previously described study by Stewart et al, they demonstrated that unaware hypertensives were significantly less likely than normotensives to report chest pain, and aware hypertensives and aware (previously diagnosed with hypertension) normotensives were significantly more likely to report all types of pain than normotensives.23 This finding supports earlier studies that suggest that diagnosed patients are more likely to report more symptoms and health concerns.

Another study (n=33 105) demonstrated that aware hypertensive participants (multivariable adjusted OR 1.57, 95% CI [1.41 – 1.74]) had an elevated risk of distress (General Health Questionnaire score ≥4) compared to normotensive participants.26 Unaware hypertensives (OR 0.91, 95% CI [0.78 – 1.07]) did not have an elevated risk of distress. These findings suggest that knowledge of the diagnosis rather than hypertension itself may result in some of the elevated psychological distress.

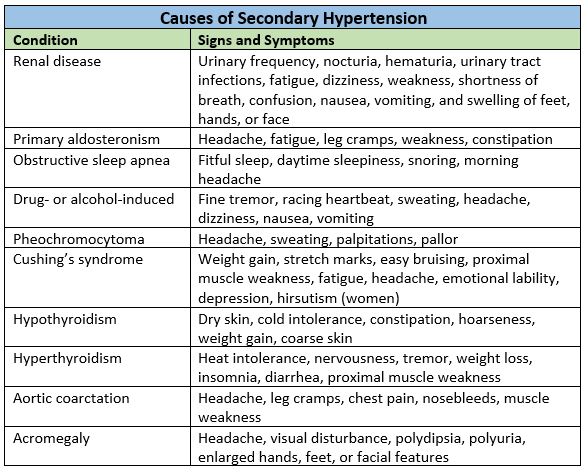

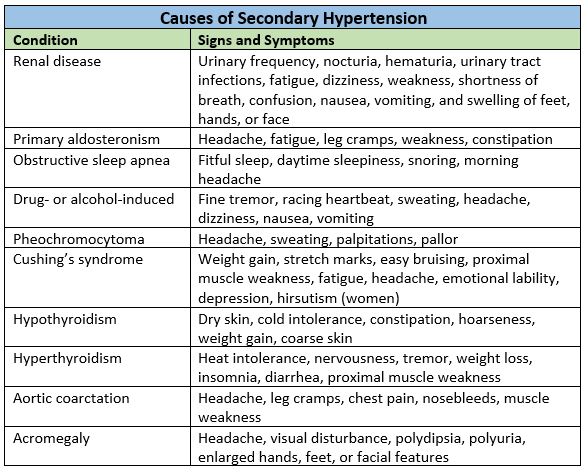

Symptoms Due to Secondary Hypertension

Up to 10% of hypertension is caused by an underlying condition.30-33 This is called secondary hypertension. These conditions often cause symptoms. Causes of secondary high blood pressure include:7

References

- Ohler WR. The signs and symptoms of hypertension. Am Heart J 1927; 2 (6): 609-612.Page IH. Hypertension: a symptomless but dangerous disease. N Engl J Med 1972; 287 (13): 665-666.

- A global brief on hypertension: silent killer, global health crisis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013.

- Siu AL. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163 (10): 778-786.

- Bell K, Twiggs J, Olin BR, Date IR. Hypertension: The silent killer: updated JNC-8 guideline recommendations. Ala Pharm Assoc 2015: 1-8.

- Sawicka K, Szczyrek M, Jastrzebska I, Prasal M, Zwolak A, Daniluk J. Hypertension–the silent killer. JPPCR 2011; 5 (2).

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2017.

- Assarzadegan F, Asadollahi M, Hesami O, Aryani O, Mansouri B, Beladi Moghadam N. Secondary headaches attributed to arterial hypertension. Iran J Neurol 2013; 12 (3): 106-110.

- Fuchs FD, Gus M, Moreira LB, Moreira WD, Goncalves SC, Nunes G. Headache is not more frequent among patients with moderate to severe hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 2003; 17 (11): 787-790.

- Weiss NS. Relation of high blood pressure to headache, epistaxis, and selected other symptoms. The United States Health Examination Survey of Adults. N Engl J Med 1972; 287 (13): 631-633.

- Hagen K, Stovner LJ, Vatten L, Holmen J, Zwart JA, Bovim G. Blood pressure and risk of headache: a prospective study of 22 685 adults in Norway. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72 (4): 463-466.

- Fagernaes CF, Heuch I, Zwart JA, Winsvold BS, Linde M, Hagen K. Blood pressure as a risk factor for headache and migraine: a prospective population-based study. Eur J Neurol 2015; 22 (1): 156-162, e110-151.

- Kottke TE, Tuomilehto J, Puska P, Salonen JT. The relationship of symptoms and blood pressure in a population sample. Int J Epidemiol 1979; 8 (4): 355-359.

- Chatellier G, Degoulet P, Devries C, Vu HA, Plouin PF, Menard J. Symptom prevalence in hypertensive patients. Eur Heart J 1982; 3 Suppl C: 45-52.

- Middeke M, Lemmer B, Schaaf B, Eckes L. Prevalence of hypertension-attributed symptoms in routine clinical practice: a general practitioners-based study. J Hum Hypertens 2008; 22 (4): 252-258.

- Vozoris NT. Insomnia symptom frequency and hypertension risk: a population-based study. J Clin Psychiatry 2014; 75 (6): 616-623.

- Vozoris NT. The relationship between insomnia symptoms and hypertension using United States population-level data. J Hypertens 2013; 31 (4): 663-671.

- Min HJ, Kang H, Choi GJ, Kim KS. Association between hypertension and epistaxis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017; 157 (6): 921-927.

- Kikidis D, Tsioufis K, Papanikolaou V, Zerva K, Hantzakos A. Is epistaxis associated with arterial hypertension? A systematic review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2014; 271 (2): 237-243.

- Knopfholz J, Lima-Junior E, Precoma-Neto D, Faria-Neto JR. Association between epistaxis and hypertension: a one year follow-up after an index episode of nose bleeding in hypertensive patients. Int J Cardiol 2009; 134 (3): e107-109.

- Traub YM, Korczyn AD. Headache in patients with hypertension. Headache 1978; 17 (6): 245-247.

- Hofman O, Kolar M, Reisenauer R, Matousek V. III. Significance of the differences in the prevalence of the subjective complaints between normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Acta Univ Carol Med (Praha) 1973; 19 (7-8): 601-615.

- Stewart JC, France CR, Sheffield D. Hypertension awareness and pain reports: data from the NHANES III. Ann Behav Med 2003; 26 (1): 8-14.

- Sigurdsson JA, Bengtsson C. Symptoms and signs in relation to blood pressure and antihypertensive treatment. A cross-sectional and longitudinal population study of middle-aged Swedish women. Acta Med Scand 1983; 213 (3): 183-190.

- Vandenburg MJ, Evans SJ, Kelly BJ, Bradshaw F, Currie WJ, Cooper WD. Factors affecting the reporting of symptoms by hypertensive patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1984; 18 Suppl 2: 189s-195s.

- Hamer M, Batty GD, Stamatakis E, Kivimaki M. Hypertension awareness and psychological distress. Hypertension 2010; 56 (3): 547-550.

- Mena-Martin FJ, Martin-Escudero JC, Simal-Blanco F, Carretero-Ares JL, Arzua-Mouronte D, Herreros-Fernandez V. Health-related quality of life of subjects with known and unknown hypertension: results from the population-based Hortega study. J Hypertens 2003; 21 (7): 1283-1289.

- Lukoschek P. African Americans' beliefs and attitudes regarding hypertension and its treatment: a qualitative study. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2003; 14 (4): 566-587.

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42 (6): 1206-1252.

- Pullalarevu R, Akbar G, Teehan G. Secondary hypertension, issues in diagnosis and treatment. Prim Care 2014; 41 (4): 749-764.

- Omura M, Saito J, Yamaguchi K, Kakuta Y, Nishikawa T. Prospective study on the prevalence of secondary hypertension among hypertensive patients visiting a general outpatient clinic in Japan. Hypertens Res 2004; 27 (3): 193-202.

- Anderson GH, Jr., Blakeman N, Streeten DH. The effect of age on prevalence of secondary forms of hypertension in 4429 consecutively referred patients. J Hypertens 1994; 12 (5): 609-615.

- Sinclair AM, Isles CG, Brown I, Cameron H, Murray GD, Robertson JW. Secondary hypertension in a blood pressure clinic. Arch Intern Med 1987; 147 (7): 1289-1293.

.png)