[NOTE: This article has been posted prior to peer review for use in an active research program. This content will be updated with a peer reviewed version as soon as it is available.]

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Lifestyle Change, and Life’s Essential 8 (LE8)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive inflammatory lung disease characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. It includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema, most caused by long-term exposure to tobacco smoke and other environmental irritants. COPD affects more than 15 million people in the United States and is a leading cause of hospitalizations and mortality.1COPD is strongly associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). In a large meta-analysis of 29 studies, individuals with COPD had significantly higher odds of ischemic heart disease (OR ~2.5), heart failure (OR ~4), and arrhythmias compared to those without COPD.2 In fact, CVD is a leading cause of death among COPD patients, often surpassing respiratory failure.3 The shared risk factors, such as smoking, physical inactivity, metabolic syndrome, and systemic inflammation, underline the need for coordinated care strategies that address both cardiopulmonary health.

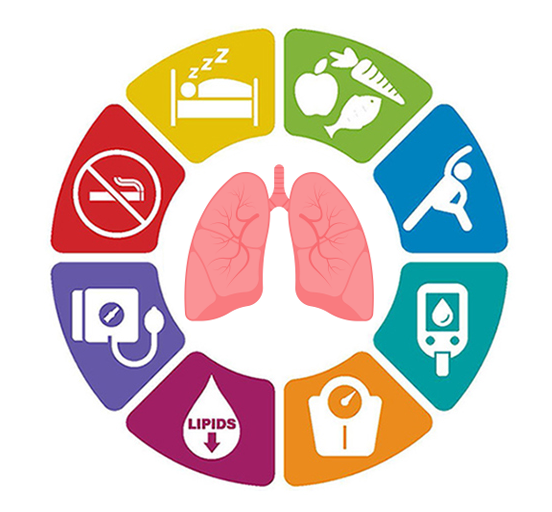

The Life’s Essential 8 (LE8) score was developed by the American Heart Association to provide a comprehensive framework for cardiovascular health across eight domains: smoking status, physical activity, diet quality, sleep health, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, blood glucose (HbA1c), and non-HDL cholesterol.4 Several of the lifestyle domains are important for COPD management as well, and in addition help decrease CVD risk, which often co-exists with COPD.

Impact of Healthy Behaviors Measured by Life’s Essential 8 on COPD Progression and Symptom Control

Lifestyle modifications have been shown to play a key role in slowing disease progression and reducing symptom burden in COPD. The lifestyle modifications discussed below (smoking cessation, physical activity, sleep, nutrition) are all measured in the LE8 score.

Smoking cessation is the most effective intervention: in long-term studies, individuals who quit smoking had a significantly slower decline in FEV₁ and were less likely to experience exacerbations or die from COPD-related causes.5,6 Even among long-term smokers, quitting led to reduced risk of hospitalization and improved survival.7

Physical activity is another evidence-based intervention that improves outcomes in COPD. A prospective study following over 6,000 individuals found that moderate to high levels of physical activity were associated with lower risk of COPD development and progression, especially in active smokers (OR 0.77, 95% CI [0.61–0.97]).8 Regular movement, including walking, improves endurance, reduces dyspnea, and lowers the rate of hospital admissions.9

Sleep disturbances, including obstructive sleep apnea, are common in COPD and linked to worse symptoms, fatigue, and higher risk of exacerbations.10,11 Treating sleep disorders and improving sleep hygiene can improve overall COPD outcomes.12

Maintaining a healthy weight helps reduce overall cardiovascular risk, which frequently coexists with COPD.13 There is a higher frequency of nutritional depletion, which is defined as a low fat-free mass index (FFMI), in patients with COPD, and has shown a higher correlation with pulmonary outcomes.14 In patients experiencing muscle wasting due to lessened frequency of physical activity, nutritional supplementation, especially with high-protein and energy-rich formulations, is associated with better pulmonary function, less lung decline, and reduced risk of COPD.15,16 Therefore, COPD patients should prioritize maintaining nutritional strategies and support muscle health to improve exercise tolerance and overall quality of life.17

COPD and the Life’s Essential 8 (LE8) Health Metrics

In a 2024 cross-sectional analysis, higher LE8 scores were associated with markedly lower odds of COPD. Individuals in the highest LE8 cardiovascular health category had an 83% lower adjusted odds of COPD compared to those in the lowest category (adjusted OR 0.17, 95% CI [0.12–0.25]).18 Each 10-point increase in LE8 was associated with an increase of 50mL in FEV1 (Beta = 50; 95% CI = 32, 67) and 56 ml in FVC (Beta = 56; 95% CI = 32, 79).19 The strongest individual contributors to this association included non-smoking status, good sleep health, sufficient physical activity, and normal blood glucose levels.20 Notably, the LE8 behavior sub score (diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, sleep) demonstrated a stronger inverse association with COPD risk than the clinical sub score (BMI, blood pressure, lipids, glucose).21

These findings reinforce the importance of lifestyle-focused, multidimensional care in COPD management. By targeting the same behavioral and clinical factors included in LE8, patients may experience not only cardiovascular benefits but also improvements in lung function, fewer exacerbations, and better quality of life.

References

- CDC. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Accessed July 28, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/copd/index.html

- Chen W, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, FitzGerald JM. Risk of cardiovascular comorbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. Aug 2015;3(8):631-9. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00241-6

- Sidney S, Sorel M, Quesenberry CP, DeLuise C, Lanes S, Eisner MD. COPD and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalizations and mortality: Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program. Chest. Oct 2005;128(4):2068-75. doi:10.1378/chest.128.4.2068

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, et al. Life's Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association's Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. Aug 02 2022;146(5):e18-e43. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001078

- Scanlon PD, Connett JE, Waller LA, et al. Smoking cessation and lung function in mild-to-moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Feb 2000;161(2 Pt 1):381-90. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9901044

- Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, et al. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. JAMA. Nov 16 1994;272(19):1497-505.

- Tashkin DP, Rennard S, Hays JT, Ma W, Lawrence D, Lee TC. Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in patients with mild to moderate COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Chest. Mar 2011;139(3):591-599. doi:10.1378/chest.10-0865

- Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Antó JM. Regular physical activity modifies smoking-related lung function decline and reduces risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Mar 01 2007;175(5):458-63. doi:10.1164/rccm.200607-896OC

- Benzo R, Hoult J, McEvoy C, et al. Promoting Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Wellness through Remote Monitoring and Health Coaching: A Clinical Trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. Nov 2022;19(11):1808-1817. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202203-214OC

- Budhiraja R, Javaheri S, Parthasarathy S, Berry RB, Quan SF. The Association Between Obstructive Sleep Apnea Characterized by a Minimum 3 Percent Oxygen Desaturation or Arousal Hypopnea Definition and Hypertension. J Clin Sleep Med. Sep 15 2019;15(9):1261-1270. doi:10.5664/jcsm.7916

- Marin JM, Soriano JB, Carrizo SJ, Boldova A, Celli BR. Outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: the overlap syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Aug 01 2010;182(3):325-31. doi:10.1164/rccm.200912-1869OC

- Zhao Q, Meng M, Kumar R, et al. The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of COVID-19: A systemic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. Oct 2020;92(10):1915-1921. doi:10.1002/jmv.25889

- Schols AM, Slangen J, Volovics L, Wouters EF. Weight loss is a reversible factor in the prognosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Jun 1998;157(6 Pt 1):1791-7. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9705017

- Gologanu D, Ionita D, Gartonea T, Stanescu C, Bogdan MA. Body composition in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Maedica (Bucur). Mar 2014;9(1):25-32.

- van de Bool C, Rutten EPA, van Helvoort A, Franssen FME, Wouters EFM, Schols AMWJ. A randomized clinical trial investigating the efficacy of targeted nutrition as adjunct to exercise training in COPD. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. Oct 2017;8(5):748-758. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12219

- Scoditti E, Massaro M, Garbarino S, Toraldo DM. Role of Diet in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients. Jun 16 2019;11(6)doi:10.3390/nu11061357

- Ferreira IM, Brooks D, White J, Goldstein R. Nutritional supplementation for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Dec 12 2012;12(12):CD000998. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000998.pub3

- Daniels K, Lanes S, Tave A, et al. Risk of Death and Cardiovascular Events Following an Exacerbation of COPD: The EXACOS-CV US Study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2024;19:225-241. doi:10.2147/COPD.S438893

- Zhang W, Zou M, Liang J, et al. Association of lung health and cardiovascular health (Life's Essential 8). Front Med (Lausanne). 2025;12:1481213. doi:10.3389/fmed.2025.1481213

- Lai Y, Yang T, Zhang X, Li M. Associations between life's essential 8 and preserved ratio impaired spirometry. Sci Rep. Mar 10 2025;15(1):8166. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-90381-w

- Crisan LL, Lee HM, Fan W, Wong ND. Association of cardiovascular health with mortality among COPD patients: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Respir Med Res. Nov 2021;80:100860. doi:10.1016/j.resmer.2021.100860