[NOTE: This article has been posted prior to peer review for use in an active research program. This content will be updated with a peer reviewed version as soon as it is available.]

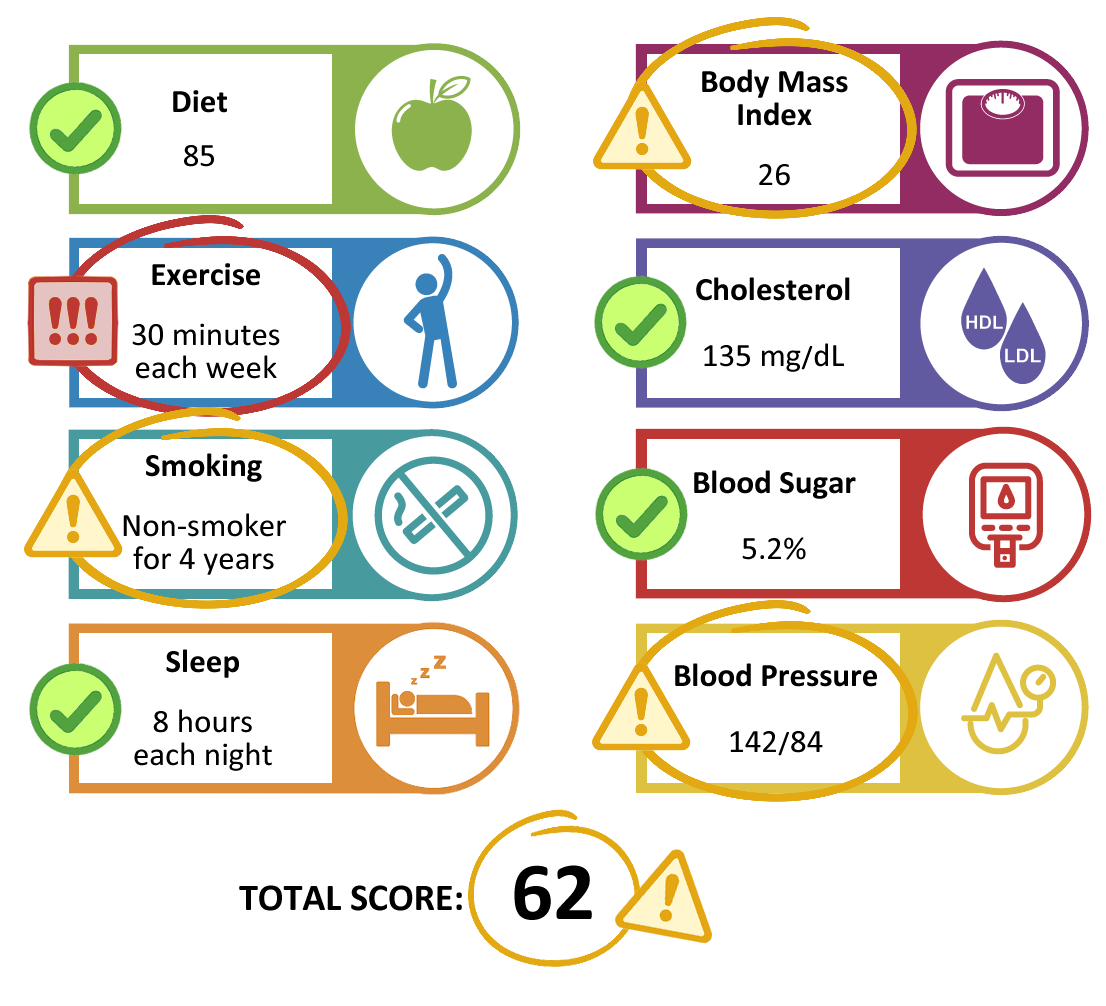

The American Heart Association (AHA) has created a quantitative assessment of cardiovascular health metrics based on Life’s Essential 8 (LE8).1 The individual areas of are each scored from 0-100 and aggregated to an overall cardiovascular health score graded from 0-100.

These LE8 scores provide a comprehensive assessment of cardiovascular health with higher scores linked to improved physiological outcomes.1 LE8 scores have been found to improve lung function, with a 10-point increase in LE8 (on the 100-point scale) associated with an increase of 50 mL in first second of forced expiration (FEV1).2 This association is furthered by improvements in non-smoking status, good sleep health, sufficient physical activity, and optimal blood glucose levels.3 With improvements in individual health risk factors, the LE8 score can help in improving cardiovascular and chronic disease health, such as COPD.

Diet (DASH)

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan emphasizes fruits, vegetable low-fat dairy, whole grains, and nuts. Another goal of the DASH diet is to reduce total and saturated fat, cholesterol, red and processed meats, and added sugars. As indicated by the name, the DASH diet was originally developed to treat hypertension but has shown benefits in lowering Coronary Heart Disease incidence (risk ratio = 0.79) and stroke incidence (risk ratio = 0.81).4 In addition, the DASH diet also has preventive benefits in lung health. Higher compliance with DASH diet is associated with lower risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, COPD (odds ratio: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.68–0.98; P = 0.033).5

Physical Activity

US Department of Health and Human Services defines sufficient physical activity as at least 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity aerobic physical activity for adults.6 A longitudinal study of 12,201 older Australian men found that higher percentage of physically active participants had lower hazard of death after 11 years (28.3% vs 40.5%) and were able to live without mood, functional, or cognitive impairment (34.9% vs 26.8%).7

Smoking Cessation

Compiling data from registries from United States, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada between 1974 and 2018, a study found that nonsmokers had better survival compared with those who smoked (12 years less in women and 13 years less in men).8 Compared with never smokers, respiratory disease (hazard ratio 6.3 in men, 7.6 in women), vascular disease (2.9 in men, 3.1 in women) and cancer (3.1 in men, 2.8 in women) were more likely to be causes of death. Respiratory disease was the cause of death in 1562 never smokers, 4222 current smokers, and 2036 former smokers. Additionally, the hazard ratio for overall mortality for former versus never smokers (1.3) was half the corresponding hazard ratio for current smokers (2.7).

Sleep Health

Nation Sleep Foundation recommend 7 to 9 hours of sleep for young adults and adults and 7 to 8 hours of sleep for older adults.9 Improvements in sleep were linked to symptom improvement and were at a reduced risk for future exacerbations.10 Patients experienced weakened sleep and insomnia were associated with higher rates of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and fills for corticosteroids, longer hospital length of stay, and $10,344 higher hospitalization costs in the 12 months after index date.11

Body Mass Index (BMI)

BMI is calculated by dividing body weight (kg) by height (m2). Maintaining a body weight of less than 25 kg/m2 is considered healthy. A health survey study in Norway found that each 5% increase in body weight is associated with approximately 20-30% higher risk of hypertension.12 Higher BMI can be associated with conditions like diabetes, gallstones, and breathing problems.13-15

Blood Lipid

There are two main types of cholesterol, or lipids, that clinicians test for: high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL). American Heart Association calculates blood lipid as fasting plasma total cholesterol subtracted by HDL cholesterol. The difference is non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dL). A meta-analysis identified that higher total and HDL-C cholesterol and CVD mortality is a linear association (pooled HR (95% CI) was 1.27 (95% CI, 1.19–1.36) for total cholesterol, 1.21 (95% CI, 1.09–1.35) for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and 0.60 (95% CI, 0.50–0.72).16

Blood Glucose

Blood glucose can be a good indicator of health, and fasting blood glucose of below 100mg/dL is considered healthy.17 A prospective cohort study of over one million Korean adults determined that men and women with blood sugar of 140 mg/dL or greater had higher risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.75; HR = 1.80).18 Participants with similar blood sugar also had a greater risk of myocardial infarction (men HR = 2.13; women HR = 3.18).

Blood Pressure

Systolic blood pressure measures the pressure of the heart contracting and diastolic blood pressure measures the pressure when the heart is resting between beats. Normal blood pressure is below 120 (systolic) and 80 (diastolic). A meta-analysis found that 10 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure is associated with reduced risk of coronary heart disease (relative risk [RR] = 0.83) and all-cause mortality (RR = 0.87).19 High blood pressure, or hypertension, also exacerbates chronic kidney disease.20

Table 1. Life's Essential 8 Cardiovascular Health Score Definitions and Distributions

|

LE8 component

|

Method of measurement

|

Criteria

|

Points

|

|

Diet

|

Harvard food frequency questionnaire; quantiles of DASH score

|

1st–24th percentile DASH

|

0

|

|

25th–49th percentile DASH

|

25

|

|

50th–74th percentile DASH

|

50

|

|

75th–95th percentile DASH

|

80

|

|

≥95th percentile DASH

|

100

|

|

Physical activity

|

Accelerometry measured minutes of moderate or vigorous activity in primary analyses (questionnaire‐based physical activity assessment evaluated in sensitivity analyses)

|

0 min of MPVA per wk

|

0

|

|

1–29 min of MPVA per wk

|

20

|

|

30–59 min of MPVA per wk

|

40

|

|

60–89 min of MPVA per wk

|

60

|

|

90–119 min of MPVA per wk

|

80

|

|

120–149 min of MPVA per wk

|

90

|

|

≥150 min of MPVA per wk

|

100

|

|

Nicotine exposure

|

Self‐reported use of cigarettes or inhaled NDS

|

Current smoker

|

0

|

|

Former smoker, quit <1 y, living with indoor smoker

|

5

|

|

Former smoker, quit <1 y, or using inhaled NDS

|

25

|

|

Former smoker, quit 1–<5 y, living with indoor smoker

|

30

|

|

Former smoker, quit 1–<5 y

|

50

|

|

Former smoker, quit ≥5 y, living with indoor smoker

|

55

|

|

Former smoker, quit ≥5 y

|

75

|

|

Never smoker, living with indoor smoker

|

80

|

|

Never smoker

|

100

|

|

Sleep health

|

Self‐reported hours of sleep per night

|

<4 h

|

0

|

|

4–<5 h

|

20

|

|

5–<6 or >10 h

|

40

|

|

6–<7 h

|

70

|

|

9–<10 h

|

90

|

|

7–<9 h

|

100

|

|

BMI

|

Body weight (kg) divided by height (m2)

|

>40.0 kg/m2

|

0

|

|

35.0–39.9 kg/m2

|

15

|

|

30.0–34.9 kg/m2

|

30

|

|

25.0–29.9 kg/m2

|

70

|

|

<25 kg/m2

|

100

|

|

Blood lipids

|

Plasma total and HDL cholesterol with calculation of non‐HDL cholesterol

|

>220 or 190–219 mg/dL and using medication

|

0

|

|

190–219 or 160–189 mg/dL and using medication

|

20

|

|

160–189 or 130–159 mg/dL and using medication

|

40

|

|

130–159 mg/dL

|

60

|

|

<130 mg/dL and using medication

|

80

|

|

<130 mg/dL

|

100

|

|

Blood glucose*

|

HbA1c (%)

|

Diabetes with HbA1c≥10.0

|

0

|

|

Diabetes with HbA1c 9.0–9.9

|

10

|

|

Diabetes with HbA1c 8.0–8.9

|

20

|

|

Diabetes with HbA1c 7.0–7.9

|

30

|

|

Diabetes with HbA1c<7.0

|

40

|

|

No diabetes and HbA1c 5.7–7

|

60

|

|

No diabetes and HbA1c < 5.7

|

100

|

|

Blood pressure

|

Systolic and diastolic BPs (mm Hg)

|

≥160 or ≥100 mm Hg

|

0

|

|

140–150 or 90–99 mm Hg and using medication

|

5

|

|

140–150 or 90–99 mm Hg

|

25

|

|

130–139 or 80–89 mm Hg and using medication

|

30

|

|

130–139 or 80–89 mm Hg

|

50

|

|

120–129/<90 mm Hg and using medication

|

55

|

|

120–129/<90 mm Hg

|

75

|

|

<120/<80 mm Hg and using medication

|

80

|

|

<120/< 80 mm Hg

|

100

|

|

We defined diabetes as either currently taking diabetes medications or having a history of diabetes. We defined no diabetes as not currently taking diabetes medication and having no history of diabetes. For 60 points, we used “No diabetes and HbA1c 5.7–7” rather than “No diabetes and HbA1c 5.7–6.4” to avoid having individuals who did not fit in any category. BMI indicates body mass index; BPs, blood pressures; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LE8, Life's Essential 8; MVPA, moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity; and NDS, nicotine‐delivery system.

|

References

- Ning H, Perak AM, Siddique J, Wilkins JT, Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB. Association Between Life's Essential 8 Cardiovascular Health Metrics With Cardiovascular Events in the Cardiovascular Disease Lifetime Risk Pooling Project. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. May 2024;17(5):e010568. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.123.010568

- Zhang W, Zou M, Liang J, et al. Association of lung health and cardiovascular health (Life's Essential 8). Front Med (Lausanne). 2025;12:1481213. doi:10.3389/fmed.2025.1481213

- Lai Y, Yang T, Zhang X, Li M. Associations between life's essential 8 and preserved ratio impaired spirometry. Sci Rep. Mar 10 2025;15(1):8166. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-90381-w

- Chiavaroli L, Viguiliouk E, Nishi SK, et al. DASH Dietary Pattern and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Nutrients. Feb 5 2019;11(2)doi:10.3390/nu11020338

- Wen J, Gu S, Wang X, Qi X. Associations of adherence to the DASH diet and the Mediterranean diet with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among US adults. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1031071. doi:10.3389/fnut.2023.1031071

- Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020-2028. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14854

- Almeida OP, Khan KM, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L. 150 minutes of vigorous physical activity per week predicts survival and successful ageing: a population-based 11-year longitudinal study of 12 201 older Australian men. Br J Sports Med. Feb 2014;48(3):220-5. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092814

- Cho ER, Brill IK, Gram IT, Brown PE, Jha P. Smoking cessation and short-and longer-term mortality. NEJM evidence. 2024;3(3):EVIDoa2300272.

- Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation's sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. Mar 2015;1(1):40-43. doi:10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010

- Lin L, Song Q, Duan J, et al. The impact of impaired sleep quality on symptom change and future exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. Mar 30 2023;24(1):98. doi:10.1186/s12931-023-02405-6

- Luyster FS, Boudreaux-Kelly MY, Bon JM. Insomnia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associations with healthcare utilization and costs. Respir Res. Mar 25 2023;24(1):93. doi:10.1186/s12931-023-02401-w

- Droyvold WB, Midthjell K, Nilsen TI, Holmen J. Change in body mass index and its impact on blood pressure: a prospective population study. Int J Obes (Lond). Jun 2005;29(6):650-5. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802944

- Chandrasekaran P, Weiskirchen R. The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-An Overview. Int J Mol Sci. Feb 4 2024;25(3)doi:10.3390/ijms25031882

- Parra-Landazury NM, Cordova-Gallardo J, Méndez-Sánchez N. Obesity and Gallstones. Visc Med. Oct 2021;37(5):394-402. doi:10.1159/000515545

- Sun Y, Zhang Y, Liu X, Liu Y, Wu F, Liu X. Association between body mass index and respiratory symptoms in US adults: a national cross-sectional study. Scientific Reports. 2024/01/10 2024;14(1):940. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-51637-z

- Jung E, Kong SY, Ro YS, Ryu HH, Shin SD. Serum Cholesterol Levels and Risk of Cardiovascular Death: A Systematic Review and a Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Jul 6 2022;19(14)doi:10.3390/ijerph19148272

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, et al. Life's Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association's Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. Aug 2 2022;146(5):e18-e43. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001078

- Park C, Guallar E, Linton JA, et al. Fasting glucose level and the risk of incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Diabetes Care. Jul 2013;36(7):1988-93. doi:10.2337/dc12-1577

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2016;387(10022):957-967. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8

- Tsuchida-Nishiwaki M, Uchida HA, Takeuchi H, et al. Association of blood pressure and renal outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease; a post hoc analysis of FROM-J study. Scientific Reports. 2021/07/22 2021;11(1):14990. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-94467-z