Dietary fiber consists of various non-digestible carbohydrates found naturally in edible plant sources, including whole grains, legumes, seeds, nuts, fruits, and vegetables.1-3 Fiber has been investigated as an isolated dietary component (e.g. grams of total dietary fiber) and more broadly as part of dietary patterns that include fiber-rich foods.

When fiber is studied as an isolated dietary component, researchers often compare outcomes in people who consume higher fiber diets to people who consume lower fiber diets. For reference, one study reported dietary fiber intake by quintiles and found the highest fiber group to consume an average of 30.1 g/day versus the lowest fiber group at 11.3 g/day.4 Currently, there is no standard definition for a high fiber diet. In this review, we will use the term “higher fiber diets” when the publication authors make comparisons between groups that contain higher versus lower intakes of dietary fiber.

We will use the term “higher fiber healthy dietary pattern” when referring to healthy dietary patterns that include relatively higher amounts of whole grains, legumes, seeds, nuts, fruits and/or vegetables.5,6 There is not a single definition for dietary patterns higher in fiber within the research literature. Several healthy diets and dietary patterns are considered to be richer in fiber, including the DASH diet and Mediterranean diet, as well as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommended healthy dietary pattern. 6,7

The research on dietary fiber and coronary heart disease (CHD) is complicated by differences in the types of fiber, food sources of fiber, and the different dietary patterns studied, leading to heterogeneity in results. However, there have been significant scientific findings regarding dietary fiber and CHD that contribute to current practice recommendations. The aim of this review was to identify the role of dietary fiber and a higher fiber dietary pattern in promoting heart health.

Methods

Two authors independently searched the literature, evidence databases and clinical practice guidelines for relevant information using established protocols. The details of the inclusion and exclusion parameters, specific databases, and search strategies are available on Open Science Framework (link here). The population included all adults, regardless of age, gender, race, or ethnicity. The literature was searched for evidence of the primary and secondary prevention effects of dietary fiber on CHD risk factors (lipid levels, blood pressure) and CHD events (atherosclerosis, heart failure, myocardial infarct, ischemic heart disease, cardiovascular disease incidence, and CHD-specific mortality). Interventions of dietary fiber as an isolated component of the diet or as part of a broader higher fiber healthy dietary pattern were included. Studies of dietary fiber supplements were excluded. Focusing on the most recent information available, only systematic reviews published within the last five years, primary literature published within the previous year, and the past ten years' most recent clinical practice guidelines were included.

We reviewed the information on the quality of the scientific evidence as reported by the authors of the systematic reviews and studies. The quality of evidence was reported using a variety of classification systems. Therefore, we normalized the quality of evidence terms reported in the text and tables of this review using the following categories: “excellent” for high GRADE[1] or strong evidence; “fair-to-good” for moderate GRADE or fair evidence; “poor” for low GRADE, very low GRADE or weak evidence; and “unclear or unrated” where authors reported insufficient evidence to evaluate, or the quality of evidence was not evaluated. Data about funding sources and author conflict of interest are noted where applicable.

Higher Dietary Fiber and Higher Fiber Healthy Dietary Patterns for Cardiovascular Health

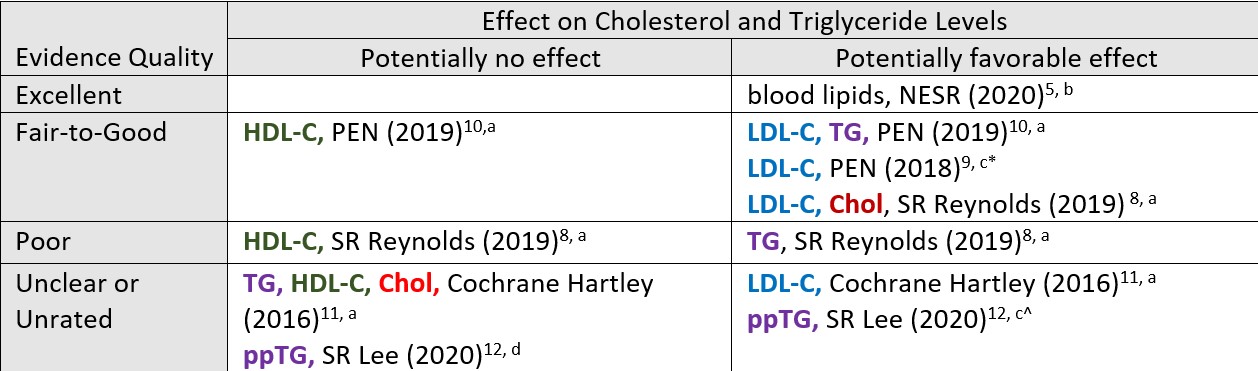

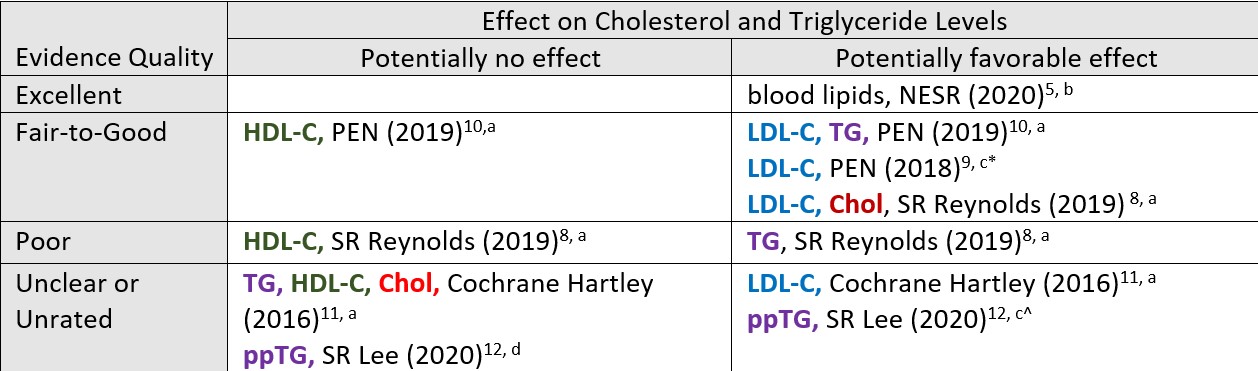

Cholesterol and Triglyceride Levels

Higher dietary fiber intake reduces total cholesterol5,8 and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C),8-11 and may decrease or have no effect on triglyceride (TG) levels.8,10-12 Types of fiber may contribute to some of the observed differences in results for TG levels. Dietary soluble fiber is associated with a decrease in postprandial TG, while dietary insoluble fiber intake does not change postprandial TG levels.12 For high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), evidence shows higher dietary fiber has no effect.8,10 Overall, the quality of evidence for studies of dietary fiber, soluble fiber and insoluble fiber was primarily fair-to-good or unclear/unrated.

Higher fiber healthy dietary patterns have a beneficial effect on blood lipid levels based on the data from one systematic review of excellent quality evidence.5

In summary, current evidence suggests possible favorable effects of dietary fiber and higher fiber healthy dietary patterns on total cholesterol, LDL-C, and TG levels, and no effect of higher dietary fiber on HDL-C. Higher dietary intake of soluble fiber, in particular, may have beneficial effects on LDL-C and TG levels. A complete list of outcomes and quality of evidence is described in Table 1a.

Table 1a. Summary of Scientific Evidence Examining the Impact of Dietary Fiber and Higher Fiber Dietary Patterns on Total Cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL and Triglyceride levels

a dietary fiber b higher fiber healthy dietary pattern c soluble dietary fiber d insoluble dietary fiber

*secondary prevention (persons with dyslipidemia); ^ Nestle funding

Abbreviations: Cochrane – Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, NESR – Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review, PEN-Practice Based Evidence in Nutrition, SR – systematic review, blood lipids – types not specified, Chol – total cholesterol, HDL-C high density lipoproteins, LDL-C-low density lipoproteins, TG-triglyceride, ppTG-postprandial triglyceride.

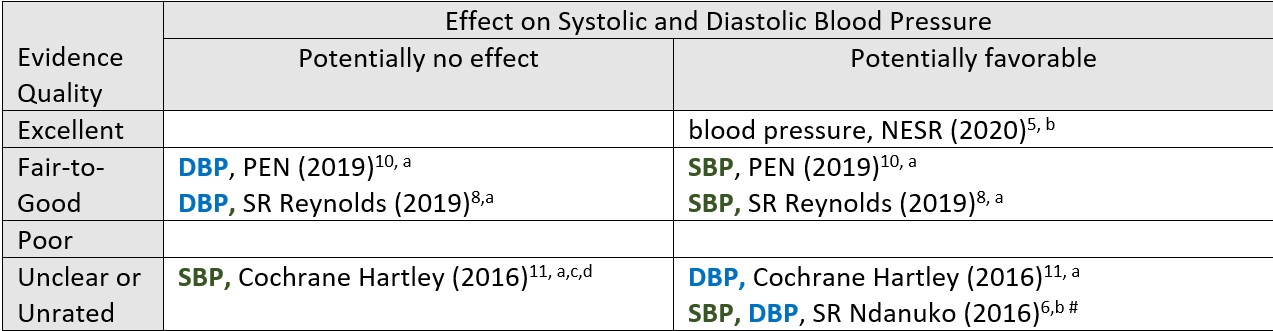

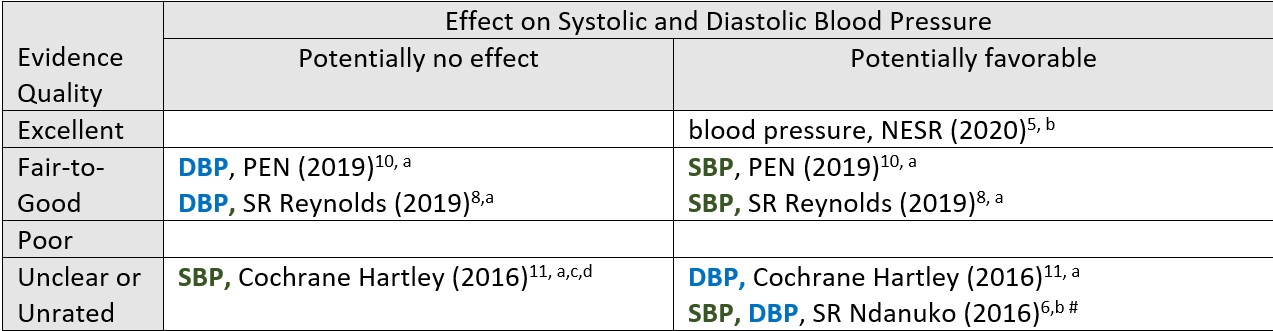

Blood Pressure

Higher dietary fiber intake may lower systolic8,10 and diastolic blood pressure11 or have no effect on systolic11 or diastolic8,10 blood pressure. There was no evidence of difference in effect with soluble versus insoluble fiber for systolic or diastolic blood pressure11. The small number of studies included in the meta-analyses and high heterogeneity in study design likely contribute to the inconsistency in the data. The quality of evidence for the studies was fair-to-good or unclear.

Higher fiber healthy dietary patterns were associated with lower blood pressure levels based on excellent quality evidence for the Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review5 and unclear quality for the systematic review by Ndanuko.6

A complete list of outcomes and quality of evidence is described in Table 1b.

Table 1b. Summary of Scientific Evidence Examining the Impact of Dietary Fiber and Higher Fiber Dietary Patterns on Blood Pressure

a dietary fiber b higher fiber healthy dietary pattern c soluble dietary fiber d insoluble dietary fiber

#high fiber dietary patterns: DASH, Nordic, Mediterranean

Abbreviations: Cochrane – Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, NESR – Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review, PEN-Practice Based Evidence in Nutrition, SR – systematic review, blood pressure – did not specify systolic or diastolic blood pressure, DBP-diastolic blood pressure, SBP-systolic blood pressure

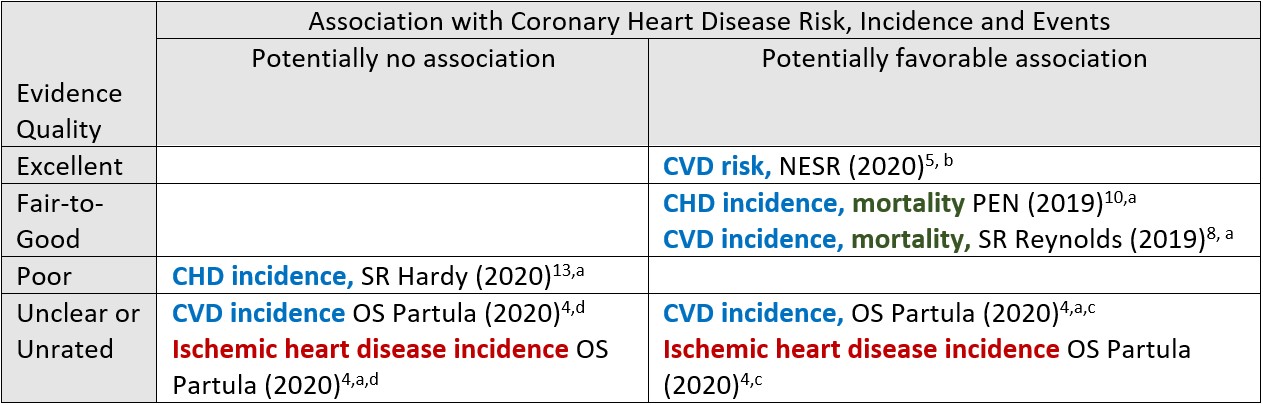

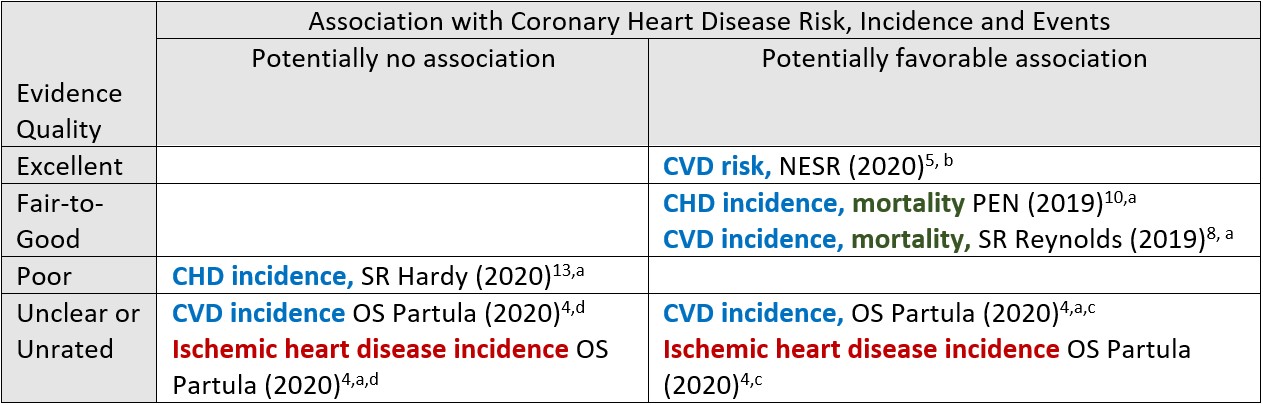

Cardiovascular Disease Events

Higher dietary fiber intake was associated with lower CHD and cardiovascular disease-related (CVD) mortality based on observational studies. 8,10 The evidence for an association with incidence of CHD, CVD and ischemic heart disease was less clear, being either potentially favorable or having no relationship.4,8,10,13 Differences in incidence outcomes may be related to the type of fiber, as suggested by the reduced incidence with higher soluble fiber intake but not with insoluble fiber intake in a recent large observational study. 4 The quality of studies on dietary fiber ranged from fair-to-good to poor, with only one study unclear/unrated.

Higher fiber healthy dietary patterns are associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk based on excellent quality evidence from one systematic review.5

Overall, a higher intake of dietary fiber is associated with lower CHD and CVD risk and mortality. The impact of dietary fiber on CHD and cardiovascular disease incidence remains unclear and may be related to fiber type. A complete list of outcomes and quality of evidence is described in Table 1c.

Table 1c. Summary of Scientific Evidence from Observational Studies Examining the Impact of Dietary Fiber and Higher Fiber Dietary Patterns on Coronary Heart Disease Risk, Incidence and Events

a dietary fiber b higher fiber healthy dietary pattern c soluble dietary fiber d insoluble dietary fiber

Abbreviations: NESR – Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review, PEN-Practice Based Evidence in Nutrition, SR-systematic review, CHD – coronary heart disease, CVD – cardiovascular disease OS – single observational study

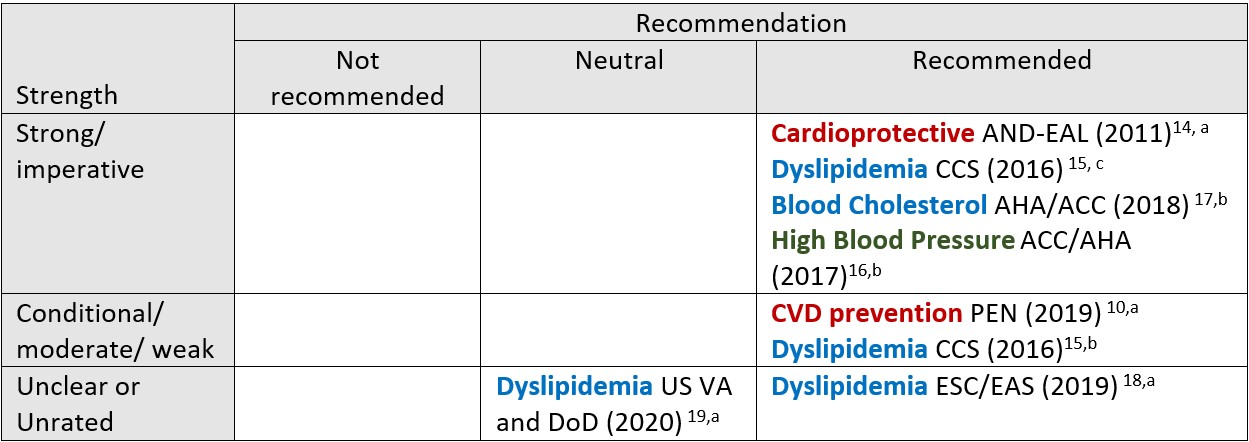

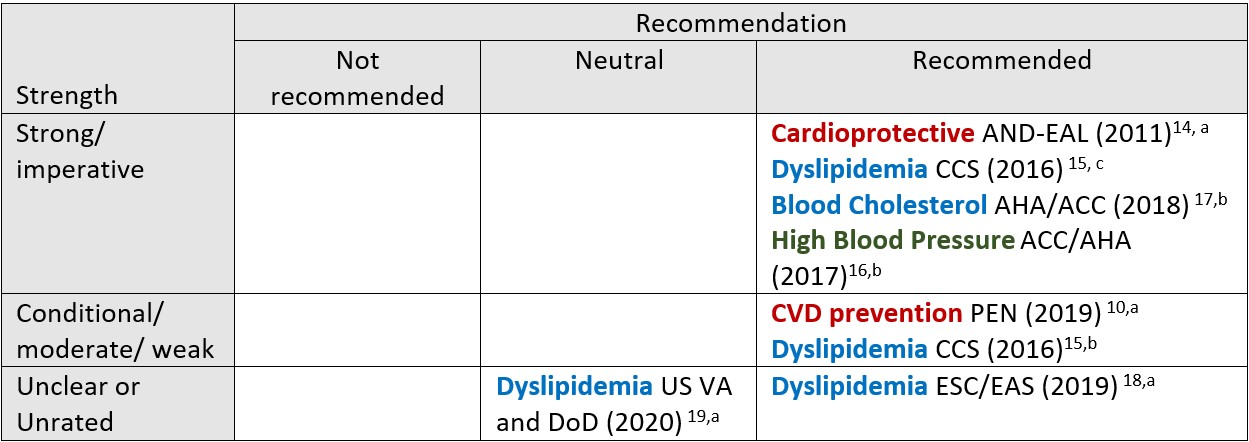

Practice Guidelines and Recommendations

Nutrition professional associations recommend dietary fiber consumption of 25 to 30 grams per day to decrease the risk for cardiovascular disease.10,14 The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics makes an additional strong recommendation for adequate soluble fiber intake of 7 to 13 grams per day.14

The American, Canadian, and European cardiovascular disease-related associations recommend higher fiber healthy dietary patterns for the management of dyslipidemia, blood cholesterol, and blood pressure.15-18 The Canadian association specifically makes a strong recommendation for a high viscous soluble fiber dietary pattern to decrease LDL-C levels.15 In contrast, the US Veterans Association and Department of Defense did not make a recommendation for or against fiber in the management of dyslipidemia due to insufficient evidence.19

Overall, both cardiovascular and nutrition society clinical practice guidelines recommend high fiber intake or a higher fiber healthy dietary pattern to prevent or manage cardiovascular disease risk. A complete list of recommendations and their associated strength are described in Table 2.

Table 2. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Recommendations for Dietary Fiber or Fiber-rich Dietary Patterns for Cardiovascular Disease

a dietary fiber b higher fiber healthy dietary pattern c soluble dietary fiber d insoluble dietary fiber

Abbreviations: AHA/ACC – American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, AND-EAL- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library, CCS-Canadian Cardiovascular Society, EAS-European Atherosclerosis Society, ESC-European Society of Cardiology, PEN-Practice Based Evidence in Nutrition, US VA and DoD- US Veteran Association and Department of Defense

Summary

A majority of the reviews suggest a potentially favorable effect of fiber on CHD risk factors and CVD mortality. The only potential unfavorable effect reported was a lowering of HDL levels.11 The quality of the evidence was most often fair-to-good or unclear/unrated, suggesting weaknesses and heterogeneity in the research methods. The vast majority of the clinical practice guidelines strongly or conditionally recommend higher fiber diets or higher fiber healthy dietary patterns for the prevention or management of CVD. Therefore, this review concludes that dietary fiber or a fiber-rich healthy dietary pattern is "heart-healthy" while recognizing that more research is needed.

References

- Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on the Definition of Dietary Fiber and the Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. Dietary Reference Intakes Proposed Definition of Dietary Fiber. . In. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

- Soliman G. Dietary Fiber, Athersclerosis, and Cardiovascular Disease. Nutreints 2019;11(5):1155.

- Ciudad-Mulero M F-RV, Matallana-González MC, Morales P. Dietary fiber sources and human benefits: The case study of cereal and pseudocereals. . Adv Food Nutr Res. 2019;90:83-134.

- Partula V, Deschasaux M, Druesne-Pecollo N, et al. Associations between consumption of dietary fibers and the risk of cardiovascular diseases, cancers, type 2 diabetes, and mortality in the prospective NutriNet-Santé cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(1):195-207.

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee and Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review Team. Dietary Patterns and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion; July 2020.

- Ndanuko RN, Tapsell LC, Charlton KE, Neale EP, Batterham MJ. Dietary Patterns and Blood Pressure in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(1):76-89.

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. DietaryGuidelines.gov. Published December 2020. Accessed April 14, 2021.

- Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Te Morenga L. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):434-445.

- Practice-based Evidence in Nutrition. In adults with elevated LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), what are the effects of the following dietary components on LDL-C levels: fibre, plant sterols, nuts, soy and pulses? Published 2018. Updated August 14, 2018. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- Practice-based Evidence in Nutrition. Are diets higher in total dietary fibre (including whole grains, cereals, vegetable, fruit and legume/pulse fibre) recommended for primary or secondary cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention? Published 2019. Updated December 10, 2019. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- Hartley L, May M, Loveman E, Colquitt J, Rees K. Dietary fibre for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. 2016. Art. No.: CD011472.

- Lee DPS, Low JHM, Chen JR, Zimmermann D, Actis-Goretta L, Kim JE. The Influence of Different Foods and Food Ingredients on Acute Postprandial Triglyceride Response: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv Nutr. 2020;11(6):1529-1543.

- Hardy DS, Garvin JT, Xu H. Carbohydrate quality, glycemic index, glycemic load and cardiometabolic risks in the US, Europe and Asia: A dose-response meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30(6):853-871.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library. What does the evidence indicate is the relationship between fiber intake and Coronary Heart Disease outcomes? https://www.andeal.org/topic.cfm?menu=5300&pcat=3742&cat=1468. Published 2011. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- Anderson TJ, Grégoire J, Pearson GJ, et al. 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in the Adult. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(11):1263-1282.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;138(17):e484-e594.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1082-e1143.

- 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. 2019;290:140-205.

- O'Malley PG, Arnold MJ, Kelley C, et al. Management of Dyslipidemia for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Reduction: Synopsis of the 2020 Updated U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(10):822-829.

.png)