Screening and follow-up are essential for cervical cancer prevention. More than 50% of cervical cancer cases in the United States occur in people who have never had screening.1 Further, follow-up after initial screening is necessary to prevent subsequent cervical cancer development. In one study, out of 344 patients with invasive cervical cancer, 33% had not had screening in the last 5 years and 15% did not have proper follow-up after a prior Pap smear.2

A Pap smear is a screening test for cervical cancer which detects both precancerous and cancerous lesions. The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) has longstanding guidelines regarding screening initiation and frequency for any person with a cervix.3

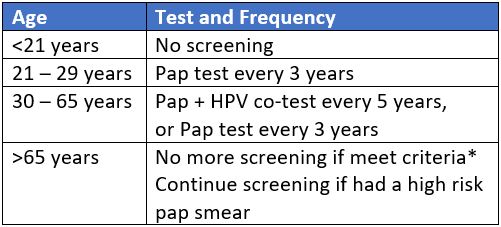

The ASCCP guidelines recommend cytology only screening pap smear every 3 years, starting at age 21 until age 30, after which cytology and HPV tests should be performed until age 65. Screening can be discontinued at age 65 as long as screening tests have been normal. Options for HPV-only screening are still debated and not yet formally recommended. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recently released guidelines that recommend initiation of Pap smears at age 25.4 This has been met with controversy due to concerns regarding missing cases of cervical cancer in young patients.

HPV infections and precancerous lesions such as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) are common among adolescents, but they have a high rate of spontaneous regression. Moscicki et al. found that, in patients aged 13 to 22, the probability of spontaneous regression of LSIL was 91% by three years.5 Additionally, most HPV infections in young patients are cleared within 4 to 14 months.6,7 These findings are reflected by the low incidence rate of cervical cancer in patients aged 15 to 19 years which was just 0.1 per 100,000 between 1998 and 2003.8 Therefore, screening is not recommended in patients younger than age 21 to reduce unnecessary intervention and avoid harms, such as overtreatment and psychological stress associated with a positive Pap smear.9

For people with a cervix aged 21 to 29 years, the ASCCP recommends cytology screening every three years.3 This interval is once again based on balancing the risks of developing cervical cancer with the harms of excessive invasive testing. The lifetime risk of death from cervical cancer is 0.03 per 1000 patients when screening is performed annually and 0.05 per 1000 patients when screening is performed every three years. However, the number of colposcopy referrals nearly doubles with annual screening.3,10 Further, there is no significant difference in the 2-year versus three-year risk for developing cervical cancer after a negative smear (odds ratio [OR] 1.2, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.65 – 2.21]).11 Thus, a 3-year screening interval allows for appropriate capture of patients at risk for development of or with early-stage cervical cancer, while limiting excessive testing on low-risk patients. At age 30, the option to perform HPV testing on Pap smear samples is available in the United States. The ASCCP does not recommend HPV testing prior to age 30 due to the high prevalence of HPV and high rate of clearance among young patients.3,6,7,12 HPV testing increases the sensitivity of detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (CIN 3) lesions or worse, and the risk of developing invasive cancer after a negative test is significantly lower.13 Specifically, Dillner et al. demonstrated that the incidence rate of CIN 3 or worse six years after negative HPV testing was 0.27%. This was significantly lower than the incidence rate of 0.97% for patients who underwent cytology alone.14 Given this data, Saslow et al. conclude that patients with a cervix who test negative for HPV are at low risk for the development of cervical cancer for at least five years.3 Therefore, it is recommended that patients aged 30 to 65 years undergo cytology and HPV co-testing at an interval of 5 years. The option of cytology screening alone can be continued after age 30, but occurs at an interval of three years. As above, this interval balances the benefits and harms of screening.

The ACS recommends primary HPV screening starting at age 25 and completed every five years thereafter.4 Similar to the ASCCP recommendations, these guidelines reflect the low incidence and mortality from cervical cancer in young patients, as well as the high incidence of transient infections. Specifically, among patients aged 21-24, Katki et al found a near zero cancer risk. Further, only 0.6% of Pap smears in this patient population demonstrated high-grade precancerous lesions.15 Additionally, moving the screening initiation to age 25 may further reduce overtreatment.16 However, guidelines change over time as more data becomes available and it is important to note that these screening intervals are not applicable after an abnormal testing result.

Screening with Pap smears or primary HPV testing is not recommended over the age of 65 for patients with at least three consecutive negative cytology screens, two consecutive negative co-tests, or two consecutive negative HPV tests within the previous ten years, with the most recent test performed within the last five years.3,4,17 The burden of invasive testing and the increased number of false positives in this patient population outweighs the risk of developing cervical cancer. The positive predictive value of Pap smears in post-menopausal patients is known to be poor.18 One modeling study demonstrated that if screening is continued until age 90, among 1,000 women, just 0.51 additional cancers would be detected, while 58 false positives and 127 colposcopies would also result.19 This, together with the median time of 15 to 25 years from new HPV infection to cervical cancer development, suggests additional screening would lead to more invasive procedures and psychological stress with little gain in cancer prevention.9,17 However, patients with a history of abnormal Pap smears with CIN 2 or higher have a 2.8-fold increased risk of developing invasive cancer up to 20 years after treatment.20 Therefore, screening should continue for another 20 years after appropriate management of abnormal Pap smears, even after the age of 65.1,12

It is important to note that certain patient populations require more frequent cervical cancer screening because of associated conditions. In patients who are immunosuppressed, such as those who have HIV or those who are on immunosuppressive medications, the risk of persistent HPV infection, and therefore cervical cancer development, is higher.21 Additionally, patients who were exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero have a higher cumulative risk of CIN 2 or worse compared to those who were not exposed.22 Therefore, screening should be done more frequently for these patient populations as the risk for development of cervical cancer outweighs the potential harms.3

References

- Spence AR, Goggin P, Franco EL. Process of care failures in invasive cervical cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2007;45(2-3):93-106. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.06.007

- Janerich DT, Hadjimichael O, Schwartz PE, et al. The screening histories of women with invasive cervical cancer, Connecticut. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(6):791-794. doi:10.2105/ajph.85.6.791

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(3):147-172. doi:10.3322/caac.21139

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. July 2020. doi:10.3322/caac.21628

- Moscicki A-B, Shiboski S, Hills NK, et al. Regression of low-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesions in young women. Lancet. 2004;364(9446):1678-1683. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17354-6

- Ho GY, Bierman R, Beardsley L, Chang CJ, Burk RD. Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(7):423-428. doi:10.1056/NEJM199802123380703

- Giuliano AR, Harris R, Sedjo RL, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and clearance of type-specific human papillomavirus infections: The Young Women’s Health Study. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(4):462-469. doi:10.1086/341782

- Watson M, Saraiya M, Benard V, et al. Burden of cervical cancer in the United States, 1998-2003. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2855-2864. doi:10.1002/cncr.23756

- Lerman C, Miller SM, Scarborough R, Hanjani P, Nolte S, Smith D. Adverse psychologic consequences of positive cytologic cervical screening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165(3):658-662. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(91)90304-a

- Stout NK, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Ortendahl JD, Goldie SJ. Trade-offs in cervical cancer prevention: balancing benefits and risks. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(17):1881-1889. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.17.1881

- Miller MG, Sung H-Y, Sawaya GF, Kearney KA, Kinney W, Hiatt RA. Screening interval and risk of invasive squamous cell cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(1):29-37. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02454-7

- Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297(8):813-819. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.813

- Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(3):249-257. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70360-2

- Dillner J, Rebolj M, Birembaut P, et al. Long term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a1754. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1754

- Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, et al. Five-year risk of CIN 3+ to guide the management of women aged 21 to 24 years. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(5 Suppl 1):S64-8. doi:10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182854399

- Landy R, Birke H, Castanon A, Sasieni P. Benefits and harms of cervical screening from age 20 years compared with screening from age 25 years. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(7):1841-1846. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.65

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e111-30. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001708

- Sawaya GF, Grady D, Kerlikowske K, et al. The positive predictive value of cervical smears in previously screened postmenopausal women: the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS). Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(12):942-950. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-133-12-200012190-00009

- Kulasingam SL, Havrilesky LJ, Ghebre R, Myers ER. Screening for cervical cancer: a modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(2):193-202. doi:10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182616241

- Soutter WP, Sasieni P, Panoskaltsis T. Long-term risk of invasive cervical cancer after treatment of squamous cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(8):2048-2055. doi:10.1002/ijc.21604

- Ghebre RG, Grover S, Xu MJ, Chuang LT, Simonds H. Cervical cancer control in HIV-infected women: Past, present and future. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;21:101-108. doi:10.1016/j.gore.2017.07.009

- Hoover RN, Hyer M, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Adverse health outcomes in women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(14):1304-1314. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1013961