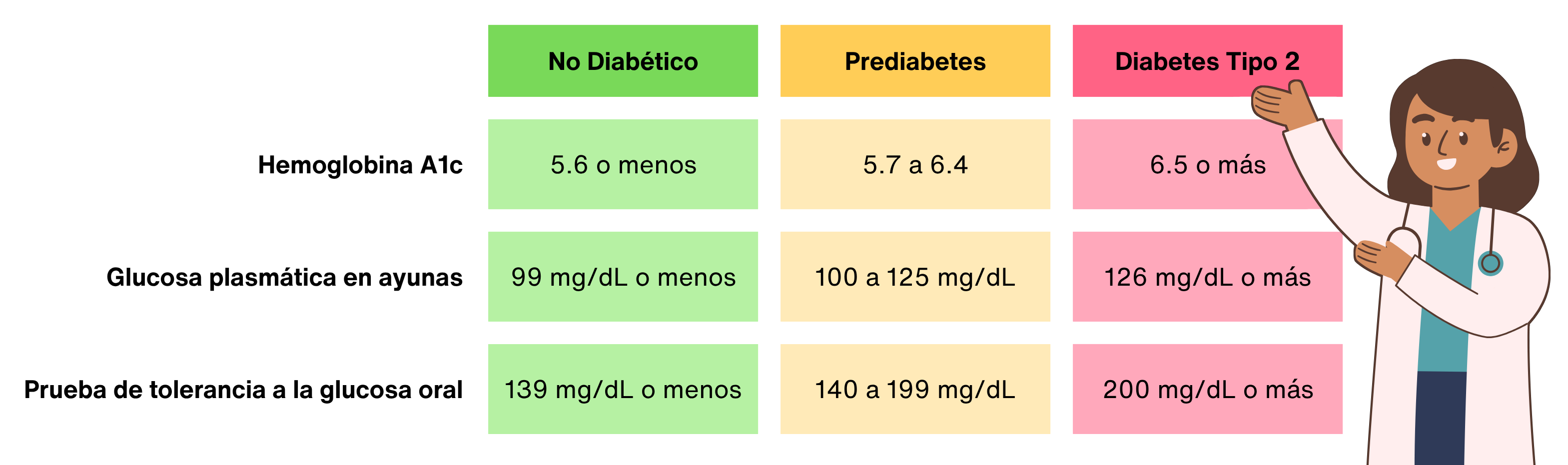

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), diabetes is diagnosed based on plasma glucose criteria (i.e., hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), Impaired Fasting Glucose [IFG] as measured by Fasting Plasma Glucose [FPG] test, or Impaired Glucose Tolerance [IGT] as measured by a 2-hour plasma glucose during 75-g Oral Glucose Tolerance Test [OGTT]).1 The exact values for diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes are outlined in the table below. Type 2 diabetes can also be diagnosed if an individual has classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis and a random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL (≥11.1 mmol/L). In the absence of demonstrable hyperglycemic symptoms, diagnosis requires confirmatory testing. Prediabetes can be diagnosed with just one test confirming dysglycemia intermediate between normoglycemia and diabetes.

Table 1. ADA criteria for the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.1

|

|

Non-Diabetic

|

Prediabetes

|

Type 2 Diabetes

|

|

Hemoglobin A1c

|

≤5.6%

≤38 mmol/mol

|

5.7-6.4%

39-47 mmol/mol

|

≥6.5%

≥48 mmol/mol

|

|

Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG)

|

≤99 mg/dL

≤5.5 mmol/L

|

100-125 mg/dL

5.6-6.9 mmol/L

|

≥126 mg/dL

≥7.0 mmol/L

|

|

2-hour Plasma Glucose during 75-g Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

|

≤139 mg/dL

≤7.7 mmol/L

|

140-199 mg/dL

7.8-11.0 mmol/L

|

≥200 mg/dL

≥11.1 mmol/L

|

International diabetes organizations follow the same diagnostic criteria as the ADA for type 2 diabetes, but some differ slightly for the diagnosis of prediabetes, also known and Intermediate Hyperglycemia (IH).1,2 The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) recommend the same threshold for OGTT but a narrower range for FPG of 110-125 mg/dL (6.1-6.9 mmol/L), and they recommend against using HbA1c for the diagnosis of prediabetes.2

Until 2003, the ADA followed international guidelines for FPG for the diagnosis of prediabetes.1 They adjusted the lower limit of FPG from 110 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L) to 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) to better align with IGT measurements in those with similar levels of risk for developing diabetes. Studies have shown that this updated threshold more accurately reflects type 2 diabetes risk. One 2008 study followed 7,211 Korean participants over two years and found that using a threshold of 110 mg/dL had a sensitivity of 53% compared to 75.3% for 100 mg/dL.3

Test Preferences

Although any two abnormal blood glucose tests are diagnostic, there is a lack of universal consensus regarding preferred screening method.2 Organizations issuing guidelines recognize the variability in availability and efficacy of testing across regions, and therefore recommend that testing be done as is situationally appropriate.1,2,4

Guidelines from the ADA as well as guidelines by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) recommend that the preferred order of diagnostic testing be HbA1c, FPG, and OGTT.1,4 The advantages of HbA1c tests are that they represent the average blood glucose over the last 120 days as well as not requiring fasting, having preanalytical stability, and being less affected by outside factors such as stress, dietary changes, or illness. However, HbA1c tests also have lesser sensitivity at lower values compared to other tests, there is limited accessibility in some parts of the world, and they are not accurate for those with certain conditions (e.g., anemia, people treated with erythropoietin, people undergoing hemodialysis, people undergoing HIV treatment, and some specific genetic variants).

The WHO emphasize the importance of retaining the OGTT as it is the only test that identifies individuals with IGT.5 Similarly, the ADA points out that most studies examining the efficacy of preventing the development of type 2 diabetes have been done on participants with IGT regardless of IFG status rather than those with isolated IFG but no IGT, highlighting the importance of OGTT testing, especially for prediabetes.1

People diagnosed with diabetes who are not dependent on insulin treatment, respond to oral diabetes treatment, and have corresponding risk factors are typically assumed to have type 2 diabetes.6 However, cases can arise where classification of diabetes type is less clear, such as in patients with similar phenotypic risk factors. In those cases, standardized testing for islet autoantibodies that only occur in people with type 1 diabetes can aid in diagnosis.1

Screening

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Diabetes Statistics Report, 97.6 million adults 18 years or older had prediabetes and 38.4 million people had diabetes in 2021, or about 11.6% and 38.0% of the adult population, respectively.7 Only 19.0% of adults with prediabetes knew they had the condition. Prediabetes and the early stages of type 2 diabetes does not have clear symptoms, which has informed the ADA’s screening recommendations of testing both asymptomatic adults with risk factors as well as otherwise healthy asymptomatic adults.

Specifically, the ADA recommends testing adults who are overweight or who have obesity who also have at least one of the following risk factors:1

- First-degree relative with diabetes

- High-risk race, ethnicity, or ancestry such as African American, Latino, Native American, or Asian American

- History of cardiovascular disease

- Hypertension or on therapy for hypertension

- HDL cholesterol level <35 mg/dL (<0.9 mmol/L) and/or triglyceride level >250 mg/dL (>2.8 mmol/L)

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- Physical inactivity

- Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance

The ADA also recommends that asymptomatic and otherwise healthy adults be screened for prediabetes at minimum every 3 years starting at age 35 with consideration for more frequent testing depending on test results and risk factors.

For those who have had gestational diabetes, they recommend testing every 1-3 years. For those with prediabetes, they recommend retesting annually. They further recommend closely monitoring individuals in other high-risk groups such as those with HIV, exposure to high-risk medicines, evidence of periodontal disease, and history of pancreatitis.

References

- 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes care. Jan 1 2025;48(1 Suppl 1):S27-s49. doi:10.2337/dc25-S002

- IDF Global Clinical Practice Recommendations for Managing Type 2 Diabetes 2025. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. Jun 2025;224:112238. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2025.112238

- Kim SH, Shim WS, Kim EA, et al. The effect of lowering the threshold for diagnosis of impaired fasting glucose. Yonsei Med J. Apr 30 2008;49(2):217-23. doi:10.3349/ymj.2008.49.2.217

- Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. Jan 7 2020;41(2):255-323. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz486

- Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia: Report of a WHO/IDF consultation . 2006.

- Butler AE, Misselbrook D. Distinguishing between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. BMJ. 2020;370:m2998. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2998

- National Diabetes Statistics Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services. Accessed 18 November 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html