Guidelines recommend that lactating individuals maintain a healthy diet.1,2 However, there is no clear significant evidence that a healthy diet can improve the quality or volume of milk production. Intake of certain foods, beverages, vitamins, and minerals can affect the composition of breastmilk, leading to recommendations regarding intake of those specific dietary components.

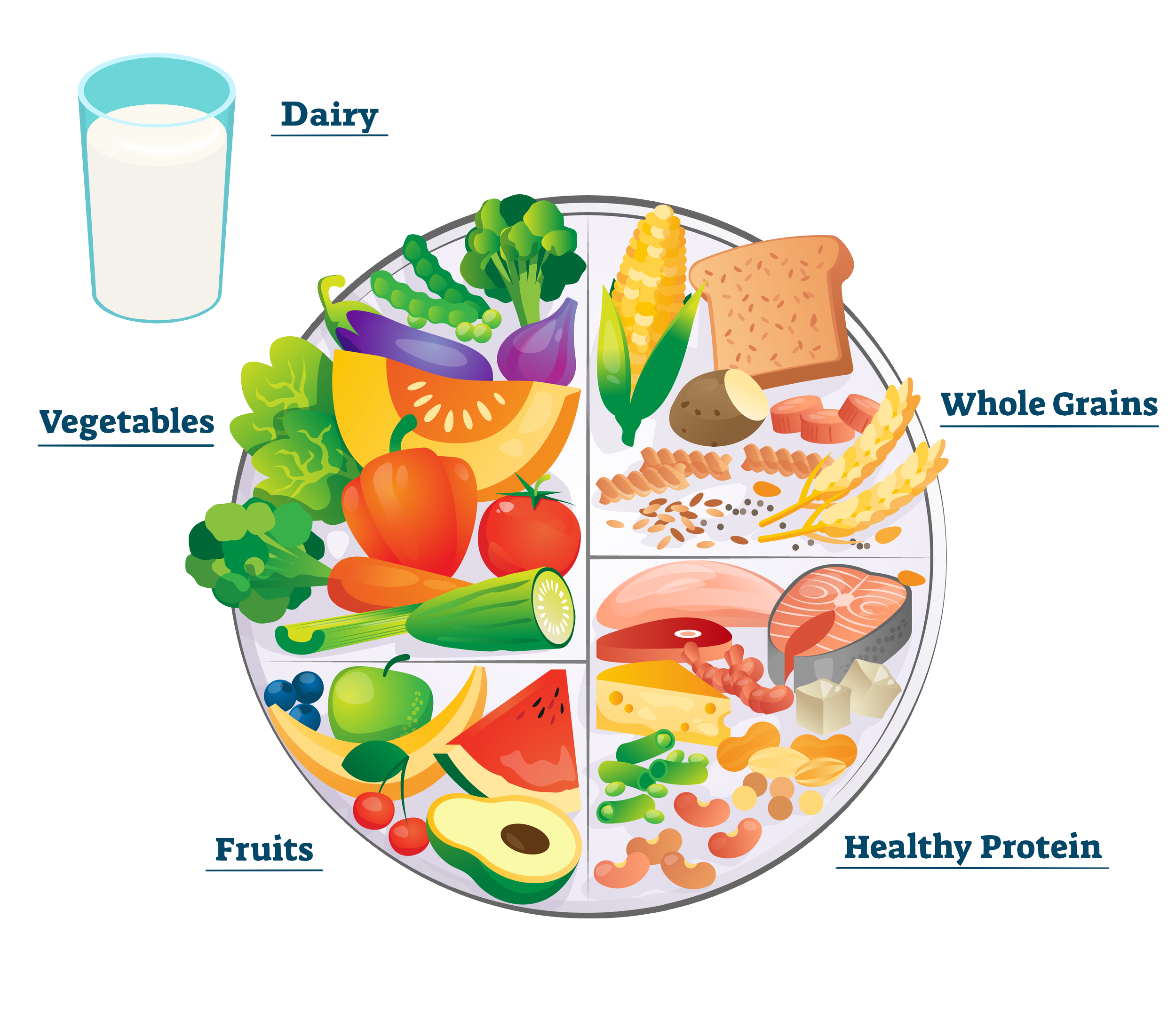

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans as well as guidelines developed by the Institute of Medicine recommend that women who are lactating maintain a healthy diet similar to that recommended for all women.1,2 Calorie needs vary based on many factors including height, weight, and level of activity, but they increase by an estimated 330 calories for the first six months of lactation and 400 calories for the second six months of lactation. Guidelines emphasize prioritizing increasing caloric intake using nutrient-dense foods. Examples of nutrient-dense foods include vegetables, fruits, whole grains, seafood, eggs, beans, peas, lentils, unsalted nuts and seeds, fat-free and low-fat dairy products, and lean meats and poultry when prepared with little or no added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium. Exact daily dietary recommendations for 1,800-2,800 calorie diets include:

- 5-3.5 cups of vegetables

- 5-2.5 cups of fruits

- 6-10 oz of grains

- 3 cups of dairy

- 5-7 oz of protein foods (meats, poultry, eggs, seafood, nuts, seeds, and soy products)

- 24-36 g of oils

- Limiting intake from other sources to 140-370 calories

Vitamins and Minerals

Certain vitamins and minerals have been found to have a corresponding affect in breastmilk, which can lead to deficiencies or exceeding the upper bounds of tolerability in newborns.1,2 The nutrients that have been found to affect breastmilk are iron, iodine, vitamin C, thiamin, vitamin B6, biotin, folate/folic acid, vitamin B12, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, and vitamin K.2 In the case of deficiencies, guidelines encourage increasing the consumption of foods that are rich in these nutrients above nutrient supplementation, but the use of supplements is recommended if deficiencies persist. They warn against the use of prenatal supplements in lactating women as they can exceed the daily recommended limit for iron and folic acid.1 The main nutrients for which supplementation are recommended include folate/folic acid, iron, iodine, choline, vitamin B12 (for vegetarian and vegan diets), and vitamin D.

During lactation, the daily recommended intake of folate/folic acid is 500 μg compared to 400 μg for nonpregnant adults.1 Folic acid is naturally found in dark green vegetables, beans, peas, and lentils. Additionally, many grains are folic acid-fortified, including bread, pasta, rice, and cereal.

During lactation, the daily recommended intake of iron is 9 mg compared to 18 mg for nonpregnant menstruating adults and 8 mg for menopausal adults.1 Heme iron, which is more easily absorbed in the body, can be found naturally in lean meats, poultry, and some seafood. Non-heme iron is found in plant sources such as beans, peas, lentils, and dark green vegetables. Absorption of non-heme iron can be enhanced by consuming it alongside vitamin C-rich foods, such as citrus fruits and dark green vegetables. Additionally, some foods are iron-enriched, including many whole wheat breads.

The daily recommended intake for iodine is 290 μg during lactation while there is no recommended iodine levels for nonpregnant adults.1 Iodine can be found in dairy products, eggs, and seafood. Additionally, most table salt is fortified with iodine. Women are not advised to increase their consumption of salt to meet their iodine needs, but they are advised to switch to iodized salt if they are not already using it.

The daily recommended intake for choline is 550 mg during lactation compared to 425 mg for nonpregnant menstruating adults and 250 mg for menopausal adults.1 Choline is found in a wide variety of food groups. Consuming the recommended amount of dairy and protein can help meet choline needs. Many prenatal supplements do not contain choline, so additional supplements may be required.

The daily recommended intake of vitamin B12 is 2.8 μg during lactation compared to 2.4 μg for nonpregnant adults. Vitamin B12 is only naturally found in foods that come from animals, including meat and eggs, so those maintaining a vegetarian or vegan diet may need to take supplements. Some cereals and nutritional yeast can also be enriched with vitamin B12.

Studies have found significant vitamin D deficiency among lactating mothers and infants aged 0-6 months. A 2015 study found that prevalence of vitamin D deficiency varies around the world, being identified in 62% of mothers and infants from Mexico (n=113 mother-infant pairs), 52% of mothers and 6% of infants from China (n=112 mother-infant pairs), and 17% of mothers and 28% of infants from the United States (n=119 mother-infant pairs) (p<0.001).3 The daily recommended intake of vitamin D is 600 international units (IU) for all adults. However, a study conducted in 2004 recommended vitamin D intake of 4,000 IU to improve nutritional vitamin D levels in both infants and mothers.4 They acknowledged that additional detailed studies would be required to calculate the optimal vitamin D supplementation for lactating women.

Alcohol

According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the safest option for those who are breastfeeding is abstaining from alcohol since alcohol can pass to infants through breastmilk.1,5 However, after a period of time related to the mothers’ weight, alcohol content in breastmilk drops back to zero. It takes between 2-3 hours for there to be no trace of alcohol in breastmilk after consuming one standard drink (12 oz [354 ml] of beer, 6 oz (177 ml) of wine, or 1.5 oz [44 ml] of liquor) and 4-6 hours for two standard drinks.5

Caffeine

There is a lack of high-quality evidence available to make evidence-based recommendations on safe maternal caffeine consumption. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans states that caffeine can pass through into breastmilk but does not adversely affect infants when consumed at 300 mg or less (2-3 cups of coffee) per day, which is considered low to moderate intake.1 Preterm and younger newborn infants metabolize caffeine very slowly so these mothers especially should limit their caffeine intake.6,7 If a mother is consuming high levels of caffeine, the infant may present with fussiness, jitteriness, and poor sleep patterns. In some cases, coffee intake of more than 450 mL daily may decrease iron concentrations in breastmilk and result in mild iron deficiency in infants.8

Seafood

While seafood consumption during lactation is recommended to help meet nutritional goals, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans cautions to avoid seafood that is high in mercury, such as swordfish, shark, and king mackerel.1 Studies have found that mercury can pass through breastmilk and poses a health risk for infants.9

Cannabis

There are insufficient data to evaluate the effects of cannabis use on infants during lactation and breastfeeding. Studies have shown that tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) can be passed on to infants through breastmilk, but there is limited information about the effect this may have on infants and their development.10-12 Similarly, there is limited information about the effect of second-hand cannabis smoke on infants. Given an absence of definitive data showing a lack of harm, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) discourage cannabis use during lactation.13,14

Allergies

Avoidance of certain foods or beverages while lactating has not been shown to decrease the risk of allergy development. Studies have shown that some choose to avoid common allergens such as milk, eggs, gluten, and nuts due to a belief that it may lower the risk of their child developing allergies to these foods. In a 2021 prospective study of 1,462 breastfeeding mothers, 16.1% of participants with no food allergies themselves avoided certain common allergens.15 However, there is no known connection between allergen avoidance in lactating mothers and decreased risk for developing allergies.16

References

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th ed: US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020.

- Nutrition during lactation. National Academy Press; 1991.

- Dawodu A, Davidson B, Woo JG, et al. Sun Exposure and Vitamin D Supplementation in Relation to Vitamin D Status of Breastfeeding Mothers and Infants in the Global Exploration of Human Milk Study. Nutrients. 2015;7(2):1081-1093.

- Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Vitamin D requirements during lactation: high-dose maternal supplementation as therapy to prevent hypovitaminosis D for both the mother and the nursing infant. Am J Clin Nutr. Dec 2004;80(6 Suppl):1752s-8s. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1752S

- Ho E, Collantes A, Kapur BM, Moretti M, Koren G. Alcohol and breast feeding: calculation of time to zero level in milk. Biology of the neonate. 2001;80(3):219-222. doi:10.1159/000047146

- Oo CY, Burgio DE, Kuhn RC, Desai N, McNamara PJ. Pharmacokinetics of caffeine and its demethylated metabolites in lactation : predictions of milk to serum concentration ratios. Pharmaceutical research. 1995;12(2):313-316. doi:10.1023/A:1016207832591

- Aranda JV, Cook CE, Gorman W, et al. Pharmacokinetic profile of caffeine in the premature newborn infant with apnea. The journal of pediatrics. 1979;94(4):663-668. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80047-5

- Muñoz LM, Lönnerdal B, Keen CL, Dewey KG. Coffee consumption as a factor in iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women and their infants in Costa Rica. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1988;48(3):645-651. doi:10.1093/ajcn/48.3.645

- Grandjean P, Jørgensen PJ, Weihe P. Human milk as a source of methylmercury exposure in infants. Environmental health perspectives. 1994;102(1):74-77. doi:10.1289/ehp.9410274

- Bertrand KA, Hanan NJ, Honerkamp-Smith G, Best BM, Chambers CD. Marijuana Use by Breastfeeding Mothers and Cannabinoid Concentrations in Breast Milk. Pediatrics. Sep 2018;142(3)doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1076

- Wymore EM, Palmer C, Wang GS, et al. Persistence of Δ-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Human Breast Milk. JAMA Pediatrics. 2021;175(6):632-634. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.6098

- Baker T, Datta P, Rewers-Felkins K, Thompson H, Kallem RR, Hale TW. Transfer of Inhaled Cannabis Into Human Breast Milk. Obstet Gynecol. May 2018;131(5):783-788. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002575

- Committee Opinion No. 722: Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Lactation. Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2017;130(4):e205-e209. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002354

- Ryan SA, Ammerman SD, O'Connor ME. Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Implications for Neonatal and Childhood Outcomes. Pediatrics. Sep 2018;142(3)doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1889

- Nordhagen LS, Løfsgaard VS, Småstuen MC, et al. Maternal food-avoidance diets and dietary supplements during breastfeeding. Nurs Open. Jan 2023;10(1):230-240. doi:10.1002/nop2.1298

- Garcia-Larsen V, Ierodiakonou D, Jarrold K, et al. Diet during pregnancy and infancy and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. Feb 2018;15(2):e1002507. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002507