According to current literature and published guidelines by national health committees including the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA), and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), there are three main steps to improve cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE):1

- Manage SLE itself using treat-to-target medication management

- Assess individual CVD risk and consider statin therapy

- Target traditional CVD risk factors (hyperlipidemia, hypertension, smoking, diabetes, healthy diet, and physical activity)

Lupus and CVD Risk

Many studies have shown that the overall risk of CVD is higher in patients with SLE than in the general population. One metanalysis of 20 studies found that those with SLE have on average a 2-fold increase compared to the general population of experiencing a cardiovascular event, including atherosclerosis, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), peripheral vascular disease, and heart failure. 2 The largest of the 20 studies analyzed (n=1,010,710) found that over seven years, patients with SLE had a 6.4% higher prevalence of CVD compared with control patients (25.6% vs 19.2%) (odds ratio [OR] 1.45, 95% CI [1.44-1.47], p<0.001). 3

Younger patients have an even steeper increase in risk due to the relatively lower level of CVD rates in young women as compared to the age matched population. Women aged 20-29 had a 6% increase in CVD incidence (0 vs 6%), 30-39 increased 8% (2 vs 10%), 40-49 8% (10 vs 18%), 50-59 7% (20 vs 27%), 60-69 6% (30 vs 36%), 70-79 4% (40 vs 44%), and 80-89 5% (45 vs 50%). Men aged 20-29 had a 6% increase in CVD incidence (2 vs 8%), 30-39 increased 12% (6 vs 18%), 40-49 12% (16 vs 28%), 50-59 7% (30 vs 37%), 60-69 6% (44 vs 50%), 70-79 3% (59 vs 52%), and 80-89 4% (59 vs 63%).3

Managing SLE to Lower CVD Risk

The 2022 treat-to-target update from EULAR recommends management of SLE disease activity and targeting remission to lower CVD risk. 4 CVD risk is lower in patients with better control and management of their SLE. 4-6 One study examining 1,356 patients with SLE with no prior organ damage observed 55 new heart damage events (cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, and valvular disease) over a total of 5,183 person-years of follow-up (1.06 events per 100 person-years). 5 Those who were able to achieve Lupus Low Disease Activity States (LLDAS) for longer periods of time had fewer organ damage events, including heart damage events (those who didn’t achieve LLDAS had a rate of 2.04 CVEs per 100 person-years, <25% of the study duration in LLDAS had a rate of 1.02, 25-49% was 1.70, 50-74% was 0.79, and ≥75% was 0.27). For participants who were able to achieve clinical remission on treatment, even for only 1-25% of the study duration, incidence dropped from 1.60 events per 100 person-years to 0.83. This shows that greater disease control leads to lower incidence of CVEs.

Another study found that increased SLE disease activity is associated with higher incidence of CVEs such as heart attack and stroke.6 Among 1,874 participants with no prior history of CVD, the authors observed 134 CVEs (median follow-up 91 days, rate of 1.41 CVEs per 100 person-years). This was 2.66 times what would be expected in the general population based on Framingham risk scores (95% confidence interval [CI] [2.16-3.16], p=0.0004). Rates of CVEs were higher among participants with high disease activity calculated using the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), with those with higher scores having over double the incidence (2.49 events per 100 person-years) compared to those with lower scores (0.95 events per 100 person-years).6

A study also found that use of hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial agent that is commonly used in the treatment of SLE, has an inverse relationship with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.65, 95% CI [0.46-0.90]). 7 Of the 3,036 participants with SLE, 1,616 were treated with hydroxychloroquine. Among the hydroxychloroquine users, 42 (2.5%) participants experienced MACE compared to 261 (18.4%) non-users. This represents a 15.9% decrease in absolute risk and a 7-fold decrease in relative risk.

The use of antimalarials is also associated with decreased risk of thromboembolic events (TE). 8 A study of 482 participants with SLE had an incidence of 54 TE, 17 (32%) of which had a history of antimalarial drug use vs 37 (68%) having no prior use of antimalarials (odds ratio [OR] 0.31, 95% CI [0.13-0.71]).

Another commonly used medication in the treatment of SLE, glucocorticoids, have been shown to increase the all cause CVD risk HR = 1.74; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.64–1.84; range 1.52 for polymyalgia rheumatica and/or giant cell arteritis to 2.82 for systemic lupus erythematosus).9 Because of this, the 2022 EULAR guidelines for CVD risk management in patients with SLE recommend the termination and tapering of glucocorticoids as early as possible. 4

Assessment of CVD Risk

According to the 2022 EULAR guidelines for management of cardiovascular risk in patients with rheumatic or musculoskeletal diseases such as SLE, CVD risk assessment and treatment for people with SLE should follow the general population CVD guidelines. 4 In the United States (US), this CVD risk calculation follows the ACC/AHA guidelines. 9 The current risk assessment is the pooled cohort risk equation that calculates risk percentage of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) over the next 10 years and includes information about the patient’s age, sex, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level, systolic blood pressure (BP), and whether or not the patient is on BP medication. Adults between 40-75 years of age should be screened initially and then rescreened every 4-6 years; however, screening can be done more frequently if the clinician deems it necessary. 9

For individuals between the ages of 40-75, the recommendation to initiate a statin is based on the 10-year pooled cohort risk equation risk score. For those with a 10-year ASCVD risk score of 7.5% or above, the recommendation is to start a high intensity statin. For those with a 10-year ASCVD risk score of below 7.5%, the recommendation is to consider starting a moderate intensity statin. The target of these medications is to lower the 10-year ASCVD risk score rather than targeting a lower serum cholesterol or low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level.

The Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators performed a metanalysis of 27 trials (n=174,149) that evaluated the effects of lowering LDL cholesterol in patients at low risk of vascular disease. 10 They found that statin therapy reduces the risk of ASCVD events regardless of the baseline lipid profile, with participants with or without vascular disease having very similar absolute risk reduction (1.28% vs 1.23%). Findings indicated that overall risk rather than initial LDL level determined the magnitude of the benefit of statin treatment, with those with the highest estimated 5-year risk CVE (≥30%) having a total cholesterol reduction 0.37 mmol/L (14.3 mg/dL) greater than those in the lowest risk group (<5%).

Targeting Traditional CVD Risk Factors

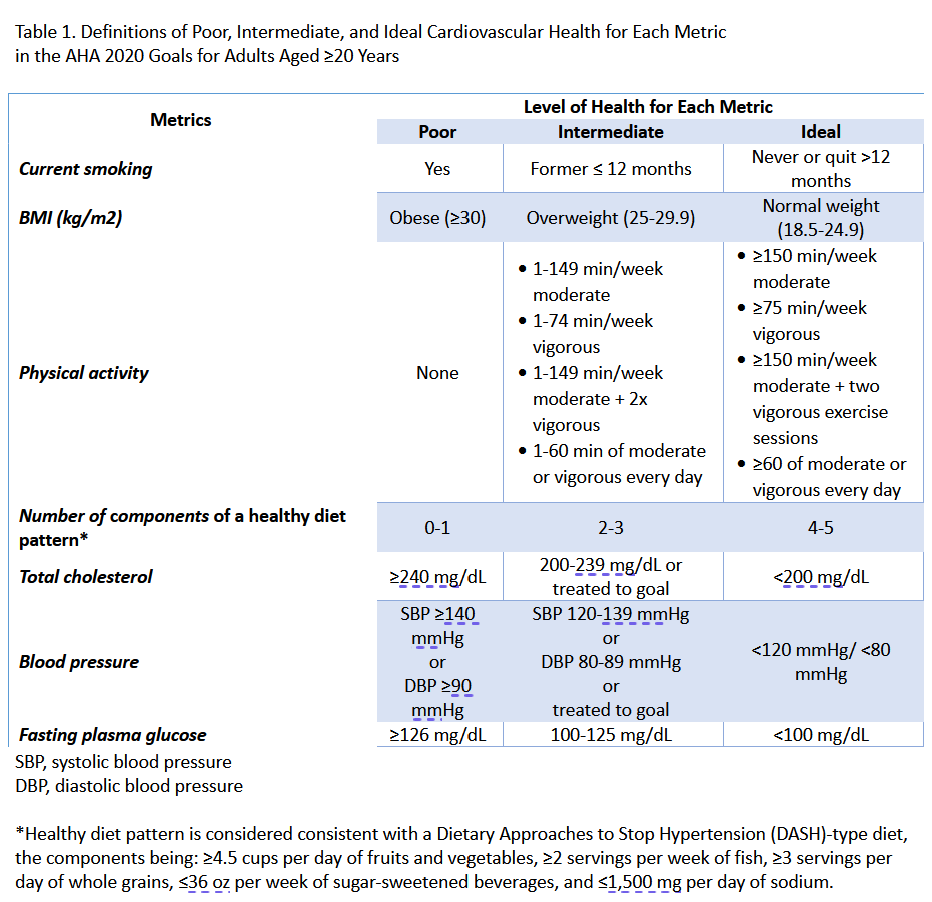

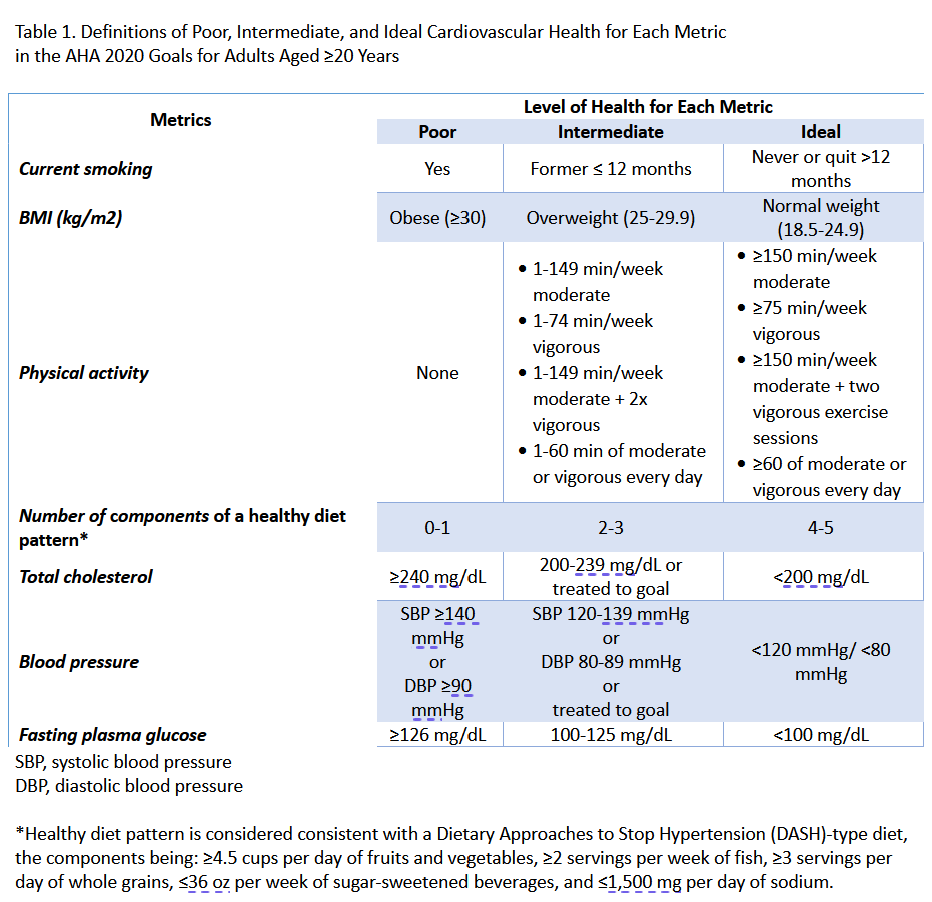

The AHA synthesized evidence-based research on achieving ideal CVD health to create Life’s Simple 7®: cholesterol, blood pressure, glucose, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, diet, and cigarette smoking.11 The biometric measurements and modifiable risk factors identified in Table 1 are the most important determinants of cardiovascular health.

These risk factors, also called traditional CVD risk factors, are shown to contribute further increase CVD risk in patients with SLE compared to the general population, possibly due to the acceleration in atherosclerosis found in those with SLE.12,13

For example, in 2010, hypertension accounted for more CVD deaths in the US than any other modifiable risk factor.14 Increased CVD risk tied to hypertension is further accentuated in those with SLE. One study of patients with SLE (n=1,532) found that those who have a sustained mean BP of ≥140/90 mm Hg over two years have a higher incidence of fatal or non-fatal coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular event, and peripheral vascular disease than those with a BP of 130-139/80-90 mm Hg or normotensive individuals (incidence rates of 1.89, 1.15, and 0.45 per 100 person-years respectively).15 This pathogenesis may be due to renal dysfunction, inflammation, and side effects from medications such as glucocorticoids.

References

- Chodara AM, Wattiaux A, Bartels CM. Managing cardiovascular disease risk in rheumatoid arthritis: clinical updates and three strategic approaches. Curr Rheumatol Rep. Apr 2017;19(4):16. doi:10.1007/s11926-017-0643-y

- Lu X, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus face a high risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. May 2021;94:107466. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107466

- Katz G, Smilowitz NR, Blazer A, Clancy R, Buyon JP, Berger JS. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Increased Prevalence of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Hospitalized Patients. Mayo Clin Proc. Aug 2019;94(8):1436-1443. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.044

- Drosos GC, Vedder D, Houben E, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2022;81(6):768-779. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221733

- Magder LS, Petri M. Incidence of and risk factors for adverse cardiovascular events among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Epidemiol. Oct 15 2012;176(8):708-19. doi:10.1093/aje/kws130

- Petri M, Magder LS. Comparison of Remission and Lupus Low Disease Activity State in Damage Prevention in a United States Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. Nov 2018;70(11):1790-1795. doi:10.1002/art.40571

- Haugaard JH, Dreyer L, Ottosen MB, Gislason G, Kofoed K, Egeberg A. Use of hydroxychloroquine and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with lupus erythematosus: A Danish nationwide cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. Apr 2021;84(4):930-937. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.013

- Jung H, Bobba R, Su J, et al. The protective effect of antimalarial drugs on thrombovascular events in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. Mar 2010;62(3):863-8. doi:10.1002/art.27289

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. Jun 25 2019;73(24):3168-3209. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.002

- Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. Aug 11 2012;380(9841):581-90. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60367-5

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. Feb 2 2010;121(4):586-613. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.109.192703

- Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Grodzicky T, et al. Traditional Framingham risk factors fail to fully account for accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. Oct 2001;44(10):2331-7. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200110)44:10<2331::aid-art395>3.0.co;2-i

- Sinicato NA, da Silva Cardoso PA, Appenzeller S. Risk factors in cardiovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Cardiol Rev. Feb 1 2013;9(1):15-9. doi:10.2174/157340313805076304

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. Jun 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Tselios K, Gladman DD, Su J, Urowitz M. Impact of the new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association definition of hypertension on atherosclerotic vascular events in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. May 2020;79(5):612-617. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216764