Exercise is an integral part of pain management and is often prescribed as treatment for patients who suffer from various types of chronic pain. Current clinical practice guidelines recommend exercise therapy for patients diagnosed with chronic low back pain,1 fibromyalgia,2 osteoarthritis,3,4 and neck pain,5 but benefits are far-reaching to other conditions and comorbidities as well.6 A longitudinal population-based study (n=4,219) showed a decrease in musculoskeletal pain in those with moderate levels of physical activity; conversely, a lack of physical activity increased the risk for additional chronic pain.7,8 Similarly, a study comparing 21 systematic reviews on exercise treatment for chronic pain in adults found a significant increase in physical function (range of motion, strength, and endurance) in patients participating in exercise interventions, though duration and type of intervention varied across the 21 reviews.9

While regular low-impact exercise routines (>6 weeks) decreased pain severity and improved functionality in patients with chronic pain,10,11 individuals who do not exercise regularly may experience an initial increase in pain associated with this increased activity level.6 This initial pain worsening may create an aversion towards exercise in non-regular-exercising individuals by solidifying the connection between exercise and pain in their mind. This association exacerbates the existing barriers to exercise and inhibits the establishment of a long-term, low-impact exercise routine in patients with chronic pain.6,10

Addressing the barriers to exercise among patients with chronic pain is most effective using a multi-modal approach that incorporates biological, psychological, and social components.10 First, incorporating exercise into the lives of chronic pain patients should be executed under the guidance of a physician, with a priority for the physician on reducing the likelihood for worsening of pain, tailoring to each individual’s physical fitness level, pain tolerance, preference for activity, and methods to recover physically from exercise.10,12 Second, there are six common strategies emphasized throughout the literature that combat the biological, psychological, and social barriers associated with exercise for patients with chronic pain. These strategies advise that patients with chronic pain should:

- Engage in physical activity that is enjoyable to improve long-term adherence to exercise routines13,14

- Prioritize exercise within their daily schedule to create routine and obligation towards planned activities13,15

- Seek social support from friends and family and guidance from physicians when starting an exercise routine or program to increase accountability, safety, and reliability10,12,13,15,16

- Record planned and completed exercises daily or weekly by way of a diary, journal, or activity tracker to regularly evaluate progress and pain levels10,15

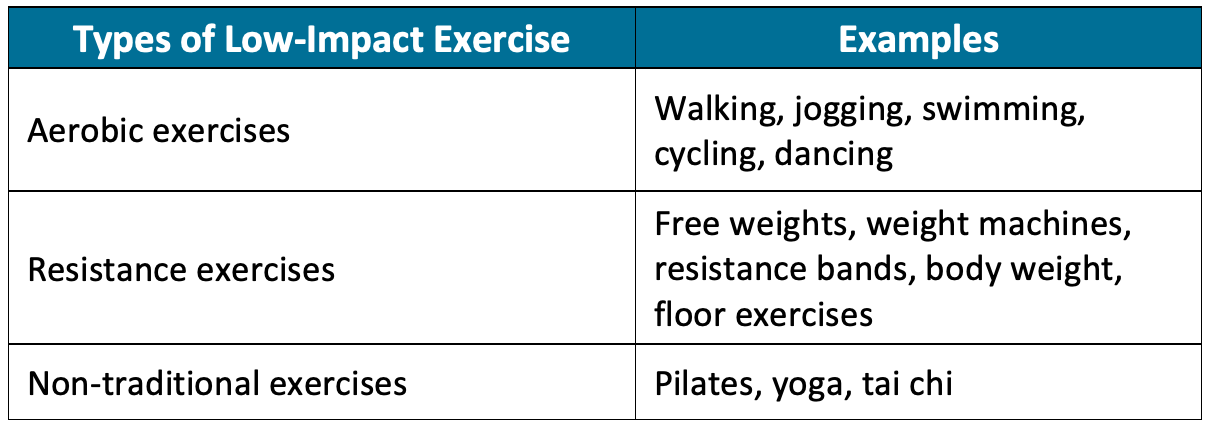

- Pace up activity by starting with low-impact aerobics (walking, jogging, swimming, cycling, dancing), resistance (free weights, weight machines, resistance bands, body weight, floor), and non-traditional (Pilates, yoga, tai chi) exercises and slowly increase intensity and duration while monitoring pain levels10,13,15

- Have adequate rest and recovery time and use methods that aid in exercise recovery such as ice, heat, and self-massage to reduce the likelihood of stress-related injury and exacerbation of pain12,13

An established exercise routine should meet the recommendations for physical activity by the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. As part of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, this committee recommends 150 to 300 minutes per week of moderate intensity physical activity.17 Patients who vary their strategies based on their pain levels and mood were more successful in establishing an exercise routine and seeing improvements in pain intensity and physical function.10,13

References:

- Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J 2018;27(11):2791-2803.

- Fitzcharles M-A, Ste-Marie PA, Goldenberg DL, et al. 2012 Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia syndrome: executive summary. Pain Res Manag 2013;18(3):119-126.

- Brosseau L, Taki J, Desjardins B, et al. The Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Part two: strengthening exercise programs. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(5):596-611.

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(4):465-474.

- Childs JD, Cleland JA, Elliott JM, et al. Neck pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(9):A1-A34.

- Sluka KA, Law LF, Bement MH. Exercise-induced pain and analgesia? Underlying mechanisms and clinical translation. Pain. 2018;159(Suppl 1):S91.

- Landmark T, Romundstad P, Borchgrevink PC, Kaasa S, Dale O. Associations between recreational exercise and chronic pain in the general population: evidence from the HUNT 3 study. Pain. 2011;152(10):2241-2247.

- Landmark T, Romundstad PR, Borchgrevink PC, Kaasa S, Dale O. Longitudinal associations between exercise and pain in the general population-the HUNT pain study. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e65279.

- Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(4).

- Booth J, Moseley GL, Schiltenwolf M, Cashin A, Davies M, Hübscher M. Exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a biopsychosocial approach. Musculoskeletal Care. 2017;15(4):413-421.

- O'Connor SR, Tully MA, Ryan B, et al. Walking exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(4):724-734.

- Daenen L, Varkey E, Kellmann M, Nijs J. Exercise, not to exercise, or how to exercise in patients with chronic pain? Applying science to practice. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(2):108-114.

- Vader K, Patel R, Doulas T, Miller J. Promoting participation in physical activity and exercise among people living with chronic pain: a qualitative study of strategies used by people with pain and their recommendations for health care providers. Pain Med. 2019;21(3):625-635.

- Jordan JL, Holden MA, Mason EE, Foster NE. Interventions to improve adherence to exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1).

- Karlsson L, Gerdle B, Takala E-P, Andersson G, Larsson B. Experiences and attitudes about physical activity and exercise in patients with chronic pain: a qualitative interview study. J Pain Res. 2018;11:133.

- Van Zanten JJV, Rouse PC, Hale ED, et al. Perceived barriers, facilitators and benefits for regular physical activity and exercise in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the literature. Sports Med. 2015;45(10):1401-1412.

- Health UDo, Services H. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. In: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Washington, DC; 2018.