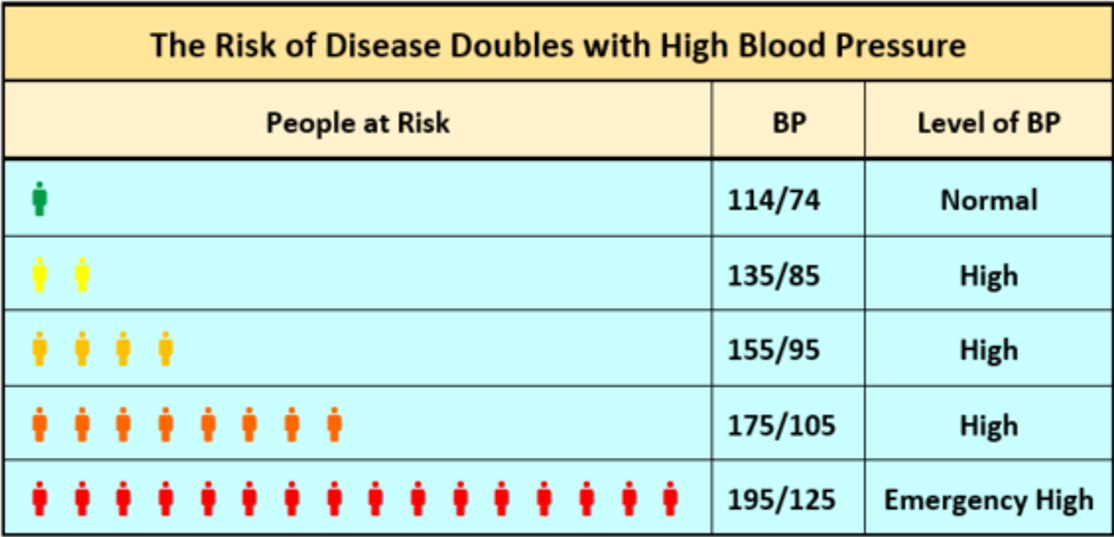

The risk for heart attack, stroke and other high blood pressure complications begins to increase around 115/75 mm Hg.1-5 The risk doubles for each 20 mm Hg increase in the systolic pressure and each 10 mm Hg increase in the diastolic pressure.1-5

Evidence shows that lowering blood pressure (BP) decreases the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes such as heart disease, stroke, and death.1,6-9 It may also slow the progression of kidney damage in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD).10 Further, meta-analyses as well as national and international guidelines suggest that lowering BP decreases risk of these outcomes regardless of which agent is used.1,6-9,11

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors Antihypertensive Effects

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are a first-line treatment for all stages of hypertension as a monotherapy or in combination with one or more other antihypertensive agents.1,6-9,12 Studies have found no significant efficacy differences between the individual ACE inhibitors.12,13

Monotherapy trials show the BP lowering efficacy of ACE inhibitors.14-19 A 2008 Cochrane Review meta-analysis found 92 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that studied the dose-related trough BP lowering efficacy of 14 ACEIs in 12 954 participants.12 The baseline BP was 157/101 mm Hg across the trials. ACE inhibitors lowered BP measured 1 to 12 hours after the dose by about 11/6 mm Hg (systolic/diastolic). The best estimate of trough BP lowering effect for ACEIs based on the largest trials was -8 mm Hg for systolic blood pressure and -5 mm Hg for diastolic blood pressure. The analysis also found that a dose of 50% of the maximum (max) daily dose had a BP lowering effect that was 90% of max and that ACE inhibitor doses above the max dose did not lower BP significantly any more than the max dose did.

A 2015 meta-analysis of 5 major antihypertensive drug classes found 12 RCTs and 13 randomized comparisons (35 707 patients) in which an ACE inhibitor was the active treatment drug.20 The review found a systolic BP/diastolic BP difference of about -4/-2 mmHg between ACE inhibitor therapy versus placebo. The average baseline BP of these studies was 157/91, with an average follow up of 3.8 years. The BP reduction was associated with significant reductions in the relative risk of all outcomes, except cardiovascular and all-cause mortalities. The analysis found a reduction of coronary heart disease (CHD) by –13% (–3 to –21%), stroke by –20% (–7 to –31%), heart failure by –21% (–7 to –34%), and major cardiovascular events (composite of stroke, CHD and heart failure) by –17% (–8 to 25%). Statistical significance was not achieved by cardiovascular mortality (11% reduction) and all-cause mortality (8% reduction).

Cardiovascular Disease Risk Reduction

Bangalore et al. performed a meta-analysis11 of 106 randomized trials of 254 301 patients without heart failure (including placebo-controlled, active-controlled, and head-to-head trials) that compared two first-line antihypertensive monotherapies, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). One important conclusion was that ACE inhibitors compared to placebo significantly reduce the outcomes of myocardial infarction (MI) (relative risk [RR] 0.83, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.78 – 0.90]), heart failure (RR 0.77, 95% CI [0.71 – 0.84]), stroke (RR 0.85, 95% CI [0.76 – 0.94]), end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (RR 0.81, 95% CI [0.70 – 0.94), new-onset diabetes (RR 0.89, 95% CI [0.84 – 0.95]), cardiovascular death (RR 0.85, 95% CI [0.79 – 0.92]), and all-cause mortality (RR 0.91, 95% CI [0.86 – 0.96]).

A 1993 multicenter randomized clinical trial of 19 394 patients assessed the efficacy of lisinopril, transdermal glyceryl trinitrate, and their combination on ventricular function and survival for 6 weeks following an acute MI.21 The study found that lisinopril started within 24 hours of the acute MI significantly reduced overall mortality compared to usual care (odds ratio [OR] 0.88, 95% CI [0.79 – 0.99]) and the combined outcome measure of mortality and severe ventricular dysfunction (OR 0.90, 95% CI [0.84 – 0.98]).

A 1987 double-blind randomized controlled trial of enalapril with 253 patients with severe heart failure, found a 27% (p=0.003) reduction in total mortality in the treated group versus the placebo group, at 6 months average follow up.22 A significant improvement with reduction of heart size and reduced need for other heart failure medication was seen in the enalapril group.

A 1993 double-blind randomized controlled trial of enalapril on 108 patients with left ventricular ejection fraction ≤0.35 but without clinical heart failure found that enalapril slows or reverses left ventricular dilatation in asymptomatic patients.23 Radionuclide end-diastolic volume decreased in enalapril patients (120 ± 25 to 113 ± 25 mL/m2, mean ± SD) but increased in placebo patients (119 ± 28 to 124 ± 33 mL/m2) at 25 months.

Heart failure management guidelines recommend the inhibition of angiotensin by an ACE inhibitor or an ARB as a key component of the treatment plan for people with hypertension and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).24-26 Studies have shown that ACE inhibitors may reduce heart failure hospitalizations and death in people with HFrEF.27-31

Kidney Disease Risk Reduction

Studies have shown that the progression of kidney disease may be slowed by ACE inhibitors by reducing blood pressure, reducing proteinuria, improving renal blood flow, and improving intraglomerular pressure due to the vasodilatory effects of ACE inhibitors.32-35

A 2015 network meta-analysis of randomized trials examined the effect of antihypertensives on all-cause mortality and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in adults with diabetic kidney disease.35 It found ARB monotherapy reduced progression to end-stage renal disease in people with diabetes compared to placebo (OR 0.77, 95% CI [0.65 – 0.92]), but ACE inhibitor monotherapy just barely missed statistical significance (OR 0.71, 95% CI [0.51-1.01]). Combination therapy with ARB and ACE inhibitor was superior (OR 0.62, 95% CI [0.43-0.90]), but this combination has some risk of increased hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury.

A 1999 double-blind placebo controlled trial of 186 patients with chronic non-diabetic nephropathy and persistent proteinuria found that progression to ESRD was significantly less in the ramipril group than placebo group (9.1% vs 20.7%, risk ratio [RR] 2.72, 95% CI [1.22 – 6.08]).34 Progression to overt proteinuria was also less in the ramipril group (15/99 vs 27/87, RR 2.40, 95% CI [1.27–4.52]).

A 1996 randomized controlled trial of 583 patients with renal insufficiency from a variety of underlying diseases including glomerulopathies, interstitial nephritis, and diabetes found that benazepril slowed the progression of renal insufficiency except in patients with polycystic kidney disease.33 Overall unadjusted risk reduction of progressive renal insufficiency was 53% in the benazepril group (71% in those with mild insufficiency and 46% with moderate).

A prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of captopril on 147 normotensive patients with type 1 diabetes with persistent albumin excretion 20 to 200 mcg/min over 24 months found that 6.0% (4/67) of patients on captopril and 18.6% (13/70) of patients on placebo progressed to clinical proteinuria.32 The albumin excretion rate decreased annually by 17.9% (95% CI [-29.6% – -4.3%]) for people taking captopril, while it increased 11.8% (95% CI [-3.3% – 29.1%]) in the placebo group (p=0.004).

Type 2 Diabetes Risk Reduction

A 2007 network meta-analysis36 of 22 clinical trials (n=143 153) looked at the incidence of new-onset diabetes in patients treated with different antihypertensive class agents or placebo. It showed the lowest incidence of new-onset diabetes occurred in those who were treated with an ACE inhibitor (OR 0.67, 95% CI [0.56 – 0.80], p<0.0001) or an ARB (OR 0.57, 95% CI [0.46 – 0.72], p<0.0001).

Roy J et al. compared a cohort of 25 035 patients with hypertension who were newly prescribed an ACE inhibitor or an ARB.37 They found no significant differences for either group for the risk of stroke, CHD, CKD, or death. They did find ARBS had a higher rate of new-onset diabetes than patients on ACE inhibitors (hazard ratio 1.28, 95% CI [1.08 – 1.52]).

Dementia

A 2016 meta-analysis38 was performed on ten randomized controlled trials and observational studies that reported the effects of either ARBs or ACE inhibitors on the development of Alzheimer disease (AD) or the cognitive impairment of aging in hypertensive patients with no pre-existing neurological deficits. The use of any renin-angiotensin system blocker (RASB) was significantly associated with a reduced risk of AD (risk ratio 0.80; 95% CI [0.68–0.92) and cognitive impairment of aging (RR, 0.65;95%CI [0.35–0.94]) compared to no use of RASB. The follow up periods of the individual studies ranged from 3-8 years.

A 2016 cohort study39 compared the dementia risk in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension between these cohorts: receiving ARBs (n=1780) versus an equal cohort of patients not receiving ARBs and receiving ACE inhibitors (n=2377) versus an equal cohort of patients not receiving ACE inhibitors. The authors found a reduction in all-cause dementia and vascular dementia for ACE inhibitor treatment (HR 0.74, 95% CI [0.74 – 0.96]) as well as for ARBs.

References

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2017.

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002; 360 (9349): 1903-1913.

- Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1.25 million people. Lancet 2014; 383 (9932): 1899-1911.

- Reboussin DM, Allen NB, Griswold ME, et al. Systematic review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017.

- Wright JT, Jr., Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373 (22): 2103-2116.

- Ahluwalia M, Bangalore S. Management of hypertension in 2017: targets and therapies. Curr Opin Cardiol 2017; 32 (4): 413-421.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults. JAMA 2014; 311 (5): 507-520.

- Pignone M, Viera AJ. Blood pressure treatment targets in adults aged 60 years or older. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166 (6): 445-445.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, Humphrey LL, Frost J, Forciea MA. Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166 (6): 430-430.

- KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2013; 3 (1): i-150.

- Bangalore S, Fakheri R, Toklu B, Ogedegbe G, Weintraub H, Messerli FH. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers in patients without heart failure? Insights from 254,301 patients from randomized trials. Mayo Clin Proc 2016; 91 (1): 51-60.

- Heran BS, Wong MM, Heran IK, Wright JM. Blood pressure lowering efficacy of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (4): Cd003823.

- Powers BJ, Coeytaux RR, Dolor RJ, et al. Updated report on comparative effectiveness of ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and direct renin inhibitors for patients with essential hypertension: much more data, little new information. J Gen Intern Med 2012; 27 (6): 716-729.

- Guitard C, Lohmann FW, Alfiero R, Ruina M, Alvisi V. Comparison of efficacy of spirapril and enalapril in control of mild-to-moderate hypertension. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1997; 11 (3): 449-457.

- Persson B, Stimpel M. Evaluation of the antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of moexipril, a new ACE inhibitor, compared to hydrochlorothiazide in elderly patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1996; 50 (4): 259-264.

- Gasowski J, Wilkins A, Drzewoski J, et al. Short-term antihypertensive efficacy of perindopril according to clinical profile of 3,188 patients: A meta-analysis. Cardiol J 2010; 17 (3): 259-266.

- Gradman AH, Arcuri KE, Goldberg AI, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel study of various doses of losartan potassium compared with enalapril maleate in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension 1995; 25 (6): 1345-1350.

- Ionescu DD. Antihypertensive efficacy of perindopril 5-10 mg/day in primary health care: an open-label, prospective, observational study. Clin Drug Investig 2009; 29 (12): 767-776.

- Sanders GD, Coeytaux R, Dolor RJ, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIS), angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARBS), and direct renin inhibitors for treating essential hypertension: an update. In: AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 4. Effects of various classes of antihypertensive drugs--overview and meta-analyses. J Hypertens 2015; 33 (2): 195-211.

- GISSI-3: effects of lisinopril and transdermal glyceryl trinitrate singly and together on 6-week mortality and ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'infarto Miocardico. Lancet 1994; 343 (8906): 1115-1122.

- Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med 1987; 316 (23): 1429-1435.

- Konstam MA, Kronenberg MW, Rousseau MF, et al. Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril on the long-term progression of left ventricular dilatation in patients with asymptomatic systolic dysfunction. SOLVD (Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction) Investigators. Circulation 1993; 88 (5 Pt 1): 2277-2283.

- Rosendorff C, Lackland DT, Allison M, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Society of Hypertension. Circulation 2015; 131 (19): e435-470.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68 (13): 1476-1488.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62 (16): e147-239.

- Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJV, Velazquez EJ, et al. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 2003; 349 (20): 1893-1906.

- Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008; 358 (15): 1547-1559.

- Flather MD, Yusuf S, Kober L, et al. Long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left-ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. ACE-Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. Lancet 2000; 355 (9215): 1575-1581.

- Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, Carlsen JE, et al. A clinical trial of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995; 333 (25): 1670-1676.

- Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, Hood WB, Jr., Cohn JN. Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med 1992; 327 (10): 685-691.

- Laffel LM, McGill JB, Gans DJ. The beneficial effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition with captopril on diabetic nephropathy in normotensive IDDM patients with microalbuminuria. North American Microalbuminuria Study Group. Am J Med 1995; 99 (5): 497-504.

- Maschio G, Alberti D, Janin G, et al. Effect of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor benazepril on the progression of chronic renal insufficiency. The Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibition in Progressive Renal Insufficiency Study Group. N Engl J Med 1996; 334 (15): 939-945.

- Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gherardi G, et al. Renoprotective properties of ACE-inhibition in non-diabetic nephropathies with non-nephrotic proteinuria. Lancet 1999; 354 (9176): 359-364.

- Palmer SC, Mavridis D, Navarese E, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of blood pressure-lowering agents in adults with diabetes and kidney disease: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 2015; 385 (9982): 2047-2056.

- Elliott WJ, Meyer PM. Incident diabetes in clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 2007; 369 (9557): 201-207.

- Roy J, Shah NR, Wood GC, Townsend R, Hennessy S. Comparative effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for hypertension on clinical end points: a cohort study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012; 14 (7): 407-414.

- Zhuang S, Wang HF, Wang X, Li J, Xing CM. The association of renin-angiotensin system blockade use with the risks of cognitive impairment of aging and Alzheimer's disease: A meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci 2016; 33: 32-38.

- Kuan YC, Huang KW, Yen DJ, Hu CJ, Lin CL, Kao CH. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers reduced dementia risk in patients with diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2016; 220: 462-466.

.png)