The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recognizes the importance of diet in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1 They emphasize that there is no one recommended dietary pattern; rather, recommendations should be individualized with the overall goal of promoting and supporting healthy eating patterns, emphasizing a variety of nutrient-dense foods in appropriate portions to improve overall health. Considerations for dietary recommendations that are important to the management of T2DM include achieving and maintaining body weight goals; attaining glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid goals; and delaying or preventing complications due to diabetes. They caution that any diet should maintain the pleasure of eating and to only limit food choices when indicated by the literature. They further caution against focusing on macronutrients, micronutrients, or single foods, but rather consider individuals’ overall diet.

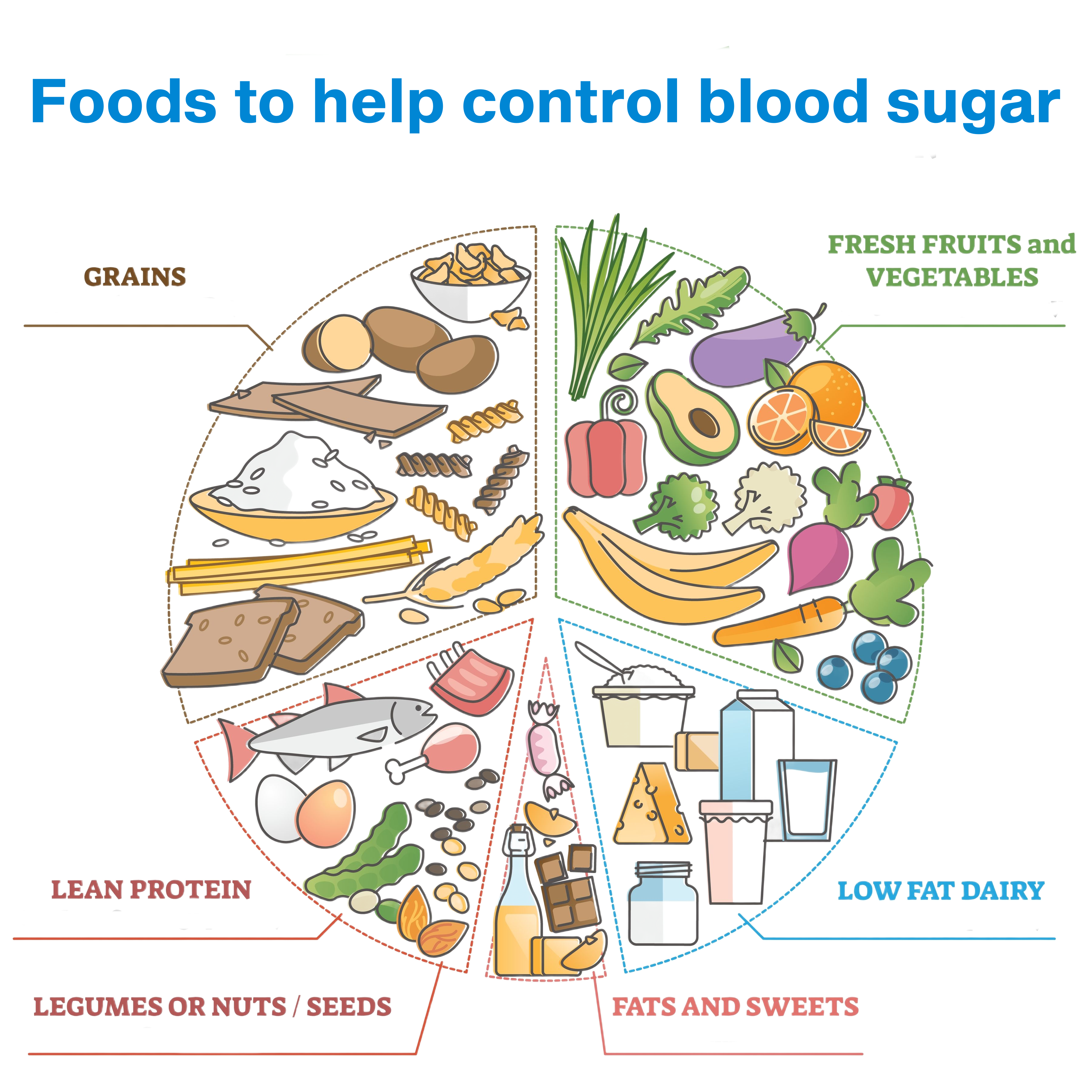

Maintaining a healthy diet can effectively aid in maintaining blood sugar within the recommended pre-prandial range of 80-130 mg/dL (4.4-7.2 mmol/L) and recommended peak postprandial capillary plasma glucose of <180 mg/dL (<10.0 mmol/L).2 Recommended eating patterns include eating a variety of foods, including different foods or food groups; preferentially eating non-starchy vegetables; minimizing added sugars and refined grains; choosing whole foods over highly processed foods whenever possible; and in certain situations, reducing overall carbohydrate intake (particularly for those whose dietary intake of carbohydrates is in excess, for those not meeting glycemic targets with other interventions, and for those who prioritize reducing medication use).1,3

There is no one recommended diet for people with T2DM, although several diets have been shown to be effective for the prevention of T2DM as well as managing blood glucose levels, including the Mediterranean diet, low-fat diets, and low-carbohydrate diets. The chart below summarizes these diets as well as the evidence supporting their use for the prevention of T2DM and management of blood glucose levels.

|

Diets for the Prevention of T2DM and Management of Blood Glucose Levels

|

|

Diet

|

Overview

|

Evidence of Risk Reduction

|

|

Mediterranean diet

|

- Olive oil as primary fat source3

- Emphasizes fruits and vegetables, whole grains, beans, nuts/seeds

- Low to moderate amounts of fish, eggs, dairy and poultry

- Limits added sugars, sodium, highly processed foods, refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, and fatty or processed meats

|

- In persons with high cardiovascular risk but without diabetes at baseline (n=3541), 16.0 cases per 1000 person-years of new-onset diabetes occurred in those following a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra virgin olive oil compared to 23.6 cases per 1000 person-years in control diet groups (absolute risk reduction of 7.6 cases per 1000 person-years).4

- In 27 subjects with T2DM randomly assigned to consume either Mediterranean diet or their usual diet for 12 weeks and then cross over to the alternate diet, on the Mediterranean intervention diet their glycosylated hemoglobin fell from 7.1% (95% CI: 6.5-7.7) to 6.8% (95% CI: 6.3-7.3) (absolute risk reduction of 0.3%; p=0.012).5

|

|

Low-fat diet

|

- Emphasizes vegetables, fruits, starches (e.g., breads/crackers, pasta, whole intact grains, starchy vegetables), lean protein sources (including beans), and low-fat dairy products, with total fat intake ≤30% of total calories and saturated fat intake ≤10%3

|

- In a randomized trial, persons considered at-risk for developing diabetes, its cumulative incidence at 6 years was 43.8% (95% CI, 35.5–52.3) in the low-fat diet group (n=130) compared to 67.7% (95% CI, 59.8–75.2) in the control group (n=133), absolute risk reduction of 23.9%).6

|

|

Low-carbohydrate diet

|

- Prioritizes low‑carbohydrate vegetables such as salad greens, broccoli, cauliflower, cucumber, and cabbage; emphasizes fats from animal sources, oils, butter, and avocado; and includes protein from meat, poultry, fish, shellfish, eggs, cheese, nuts, and seeds.3

- Certain versions allow fruit like berries and a wider selection of non‑starchy vegetables.

- Excludes starchy and sugary items including pasta, rice, potatoes, bread, and sweets.

|

- In a systematic review and meta-analysis persons (n=2412) with T2DM consuming either carbohydrate-restricted (≤45% of total energy) or high carbohydrate diets (>45% of total energy), carbohydrate-restricted diets (in particular those that restrict carbohydrate to <26% of total energy), produced greater reductions in HbA1c at 3 months (weighted mean difference (WMD) -0.47%, 95% CI: -0.71, -0.23) and 6 months (WMD -0.36%, 95% CI: -0.62, -0.09); no significant difference was observed at 12 or 24 months.7

|

|

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension for diabetes (DASH4D)

|

- Emphasize abundance of vegetables and whole fruits, whole grains with lower glycemic impact, lean proteins and plant proteins (legumes, tofu), low‑fat or unsweetened dairy, nuts and seeds, and unsaturated fats like olive oil.8

- It limits added sugars, refined carbohydrates, high‑sodium processed foods, and saturated fats, and recommends spreading carbohydrates evenly across meals and pairing them with fiber, protein, and healthy fat to reduce postprandial glucose spikes and increase time in range.8

|

- A randomized 4-period crossover feeding trial with 89 participants on continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) found that participants on the DASH4D diet had a notably lower average blood glucose level (adjusted difference of −11.1 mg/dL; 95% CI: −15.8 to −6.3; p<0.001).8

|

Variety in Diet

Eating protein and fat concurrently with carbohydrate foods lower their glycemic effect.9,10 A study conducted among 20 patients aged 7 to 17 years with type 1 diabetes found that when protein and fat were consumed 15 minutes before carbohydrates (test meal), the mean postprandial glucose levels were significantly lower compared to when all macronutrients were consumed together (standard meal). Specifically, the mean glucose levels were 1 mmol/L (18mg/dL) lower following the test meal (9.30 ± 3.20 vs. 10.24 ± 3.35 mmol/L; p<0.001). The total time period in which glucose levels exceeded 10 and 12 mmol/L (180 and 216mg/dL) was reduced by 28.7 minutes (p=0.001) and 22.3 minutes (p=0.004), respectively, after the test meal.11

A randomized three-condition crossover trial in 16 adults with type 2 diabetes who consumed the same meal on three separate days in random order: carbohydrate first, carbohydrate last (protein and vegetables first).12 When carbohydrate was eaten last, incremental glucose area under the curve (iAUC 0–180 min) was 3,124.7 ± 501.2 mg/dL×180 min versus 6,703.5 ± 904.6 mg/dL×180 min when carbohydrate was eaten first, a 53% reduction (p<0.001); incremental glucose peak was 34.7 ± 4.1 mg/dL versus 75.0 ± 6.5 mg/dL, a 54% reduction (p<0.001). Compared with the mixed (all together) condition, carbohydrate-last reduced iAUC by 44% (3,124.7 ± 501.2 vs 5,587.1 ± 828.7 mg/dL×180 min; p=0.003) and peak by 40% (34.7 ± 4.1 vs 58.2 ± 5.9 mg/dL; P < 0.001).

Non-Starchy Vegetables

Non-starchy vegetables such as leafy greens have been shown to aid in glycemic control. In a study using prospective data from 39,876 females enrolled in the Women’s Health Study, incidence of T2DM decreased from to 0.0051 cases/person-years for the lowest quintile of green leafy vegetable intake to 0.0047 cases/person-years for the highest quintile of green leafy vegetable intake (absolute risk reduction of 0.0004 cases/person-years).13,14

Added Sugars and Refined Grains

Whole-grain breads have been shown in a randomized controlled trial of patients with diabetes to produce a smaller glycemic response when compared to white bread. For example, one study (n=16) measuring the total sugar concentration of dialysis fluid three hours after bread consumption reported a trend of decreasing sugar concentration with increasing whole grant content (0.76 g/L for white bread, 0.66 g/L for barley flour bread, 0.43 g/L for 50% barley bread, 0.29 g/L for 75% barley bread, and 0.26 g/L for full barley.15

An association between total sugar intake and having diabetes was found in randomized cross-sectional analysis of adults (n = 12,800; mean age 50.5 years) drawn from the 2011 China Health and Nutrition Survey that estimated dietary intakes using three consecutive 24‑hour recalls and linked those intakes to self‑reported physician‑diagnosed diabetes.16 Baseline diabetes prevalence was 4.0%. The study found that a 1gm/day higher total sugar intake led to a 0.031% increase in the absolute risk of diabetes (Odds ratio [OR] 1.008, 95% CI [1.001-1.016]; p<0.05).

Whole Foods

Nuts contain little carbohydrate and therefore cause little postprandial glycemic response. Consuming nuts such as almonds, pistachios, or mixed nuts concurrently with carbohydrates has been demonstrated to mitigate glycemic response in a dose-dependent fashion (in 9 healthy volunteers, the addition of almonds to white bread resulted in a progressive reduction in the glycemic index of the composite meal, from 105.8 +/- 23.3 for 30 g, to 63.0 +/- 9.0 for 60 g, to 45.2 +/- 5.8 for 90 g doses of almonds (r = -0.524, n = 36, p=0.001)17; in nondiabetic patients (n=12), the addition of mixed nuts to bread progressively reduced the glycemic response of the meal by 11.2 ± 11.6%, 29.7 ± 12.2% and 53.5 ± 8.5% for the 30, 60, and 90 g doses (p=0.354, p=0.031 and p<0.001, respectively), while in subjects (n=7) with type 2 diabetes, the effect was half of that seen in the non-diabetic subjects (p=0.474, p=0.113 and p=0.015, respectively)18; addition of 56 g pistachios to carbohydrate foods significantly reduced the relative glycemic response in 10 healthy volunteers, including from 72.5±6.0 for parboiled rice, 58.7±5.1 for rice and pistachios (p=0.031), and from 94.8±11.4 for pasta to 56.4±5.0 for pasta and pistachios (p=0.025).17-19

References

- 5. Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care. Jan 1 2024;47(Suppl 1):S77-s110. doi:10.2337/dc24-S005

- 6. Glycemic Goals and Hypoglycemia: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care. Jan 1 2024;47(Suppl 1):S111-s125. doi:10.2337/dc24-S006

- Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):731-754. doi:10.2337/dci19-0014

- Salas-Salvadó J, Bulló M, Estruch R, et al. Prevention of diabetes with Mediterranean diets: a subgroup analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. Jan 7 2014;160(1):1-10. doi:10.7326/m13-1725

- Itsiopoulos C, Brazionis L, Kaimakamis M, et al. Can the Mediterranean diet lower HbA1c in type 2 diabetes? Results from a randomized cross-over study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Sep 2011;21(9):740-7. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2010.03.005

- Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. Apr 1997;20(4):537-44. doi:10.2337/diacare.20.4.537

- Sainsbury E, Kizirian NV, Partridge SR, Gill T, Colagiuri S, Gibson AA. Effect of dietary carbohydrate restriction on glycemic control in adults with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. May 2018;139:239-252. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.026

- Fang M, Wang D, Rebholz CM, et al. DASH4D diet for glycemic control and glucose variability in type 2 diabetes: a randomized crossover trial. Nature Medicine. 2025/08/05 2025;doi:10.1038/s41591-025-03823-3

- Committee ADAPP. 5. Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care. 2023;47(Supplement_1):S77-S110. doi:10.2337/dc24-S005

- Atkinson FS, Brand-Miller JC, Foster-Powell K, Buyken AE, Goletzke J. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values 2021: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. Nov 8 2021;114(5):1625-1632. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqab233

- Faber EM, van Kampen PM, Clement-de Boers A, Houdijk E, van der Kaay DCM. The influence of food order on postprandial glucose levels in children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. Jun 2018;19(4):809-815. doi:10.1111/pedi.12640

- Shukla AP, Andono J, Touhamy SH, et al. Carbohydrate-last meal pattern lowers postprandial glucose and insulin excursions in type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000440. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000440

- Evert AB, Boucher JL, Cypress M, et al. Nutrition Therapy Recommendations for the Management of Adults With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(11):3821-3842. doi:10.2337/dc13-2042

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. Sep 11-17 2004;364(9438):937-52. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(04)17018-9

- Jenkins DJ, Wesson V, Wolever TM, et al. Wholemeal versus wholegrain breads: proportion of whole or cracked grain and the glycaemic response. Bmj. Oct 15 1988;297(6654):958-60. doi:10.1136/bmj.297.6654.958

- Liu Y, Cheng J, Wan L, Chen W. Associations between Total and Added Sugar Intake and Diabetes among Chinese Adults: The Role of Body Mass Index. Nutrients. Jul 24 2023;15(14)doi:10.3390/nu15143274

- Josse AR, Kendall CW, Augustin LS, Ellis PR, Jenkins DJ. Almonds and postprandial glycemia--a dose-response study. Metabolism. Mar 2007;56(3):400-4. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2006.10.024

- Kendall CW, Esfahani A, Josse AR, Augustin LS, Vidgen E, Jenkins DJ. The glycemic effect of nut-enriched meals in healthy and diabetic subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Jun 2011;21 Suppl 1:S34-9. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2011.03.013

- Kendall CW, Josse AR, Esfahani A, Jenkins DJ. The impact of pistachio intake alone or in combination with high-carbohydrate foods on post-prandial glycemia. Eur J Clin Nutr. Jun 2011;65(6):696-702. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2011.12